How Do Lipids Support Cell Structure and Health?

Lipids play a vital role in every living organism, serving as an energy reservoir and as essential components of cell membranes. In this guide, we will explore the lipids meaning, discover what are lipids, examine the structure of lipids, discuss their functions, and the classification of lipids. We will also address a commonly asked question in biology: where do the lipids and proteins constituting the cell membrane get synthesised? By the end of this overview, you will have a clear understanding of lipids definition, their types, and their significance in living systems.

Read More: Biomolecules

Lipids Definition and Lipids Meaning

Lipids definition: Lipids are organic molecules predominantly composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. They are non-polar compounds, meaning they do not dissolve in water (which is polar), but they are soluble in non-polar solvents such as chloroform and ether.

Lipids meaning: The term “lipid” originates from the Greek word lipos, meaning “fat.” Although the word “fat” is often used informally to refer to all lipids, not all lipids are fats. Fats are one specific type of lipid, while the broader group of lipids includes oils, waxes, phospholipids, steroids, and more.

Also Check: Digestion and Absorption

What are Lipids?

Energy Storage: Lipids, especially triglycerides, provide a dense form of energy storage.

Structural Components: They are integral components of cellular membranes (e.g., phospholipids and cholesterol in animals).

Insulation and Protection: Adipose (fat) tissue cushions organs and helps maintain body temperature.

Signalling: Certain lipid derivatives act as hormones or intracellular messengers (e.g., steroid hormones).

Structure of Lipids

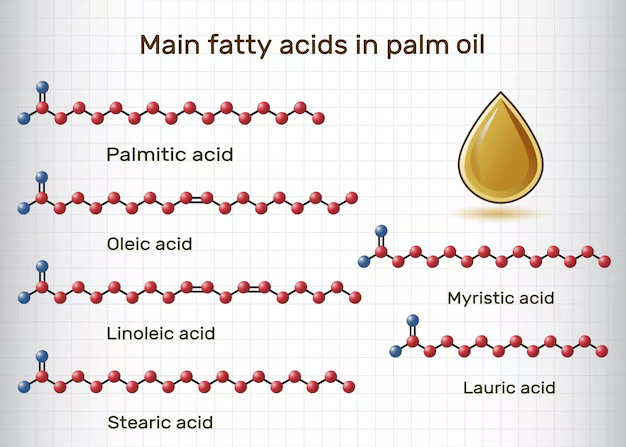

The structure of lipids can vary widely depending on their type. However, most contain one or more fatty acids, which consist of long hydrocarbon chains ending in a carboxylic acid group. Fatty acids can be:

Saturated Fatty Acids:

Possess no carbon-carbon double bonds.

Pack tightly and are typically solid at room temperature (e.g., butter, ghee).

Unsaturated Fatty Acids:

Contain one or more double bonds.

Often liquid at room temperature (e.g., most vegetable oils).

The double bonds create “kinks,” reducing tight packing.

Lipids Structure in Cell Membranes

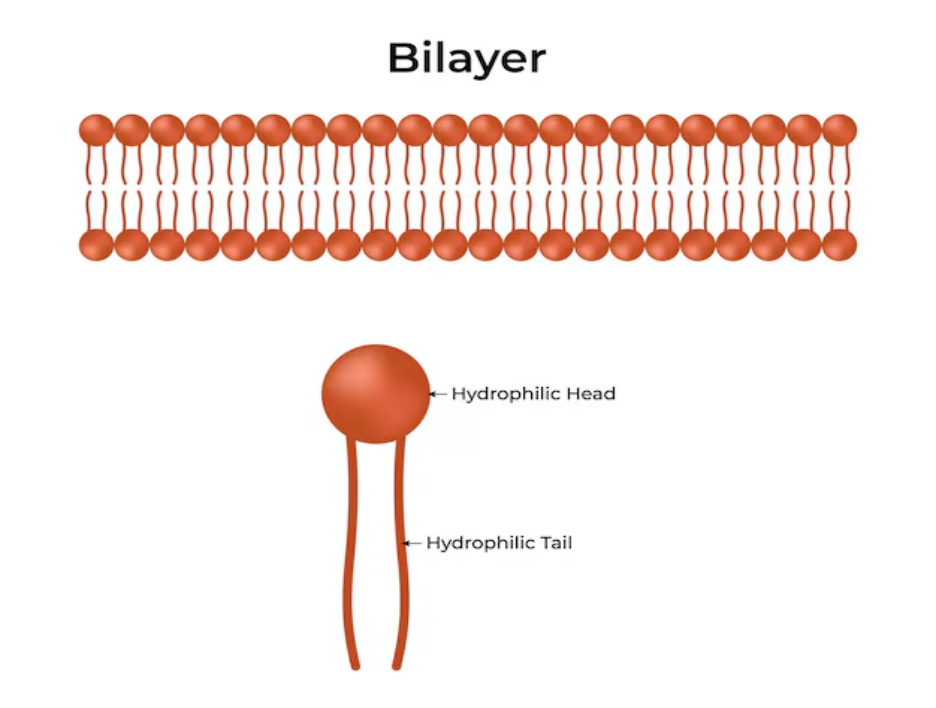

In biological membranes, the lipids structure is primarily that of phospholipids and cholesterol. Phospholipids have two fatty acid chains and a phosphate group attached to glycerol. This structure creates a hydrophilic (water-attracting) “head” and two hydrophobic (water-repelling) “tails,” facilitating the formation of a bilayer membrane.

Function of Lipids

Understanding the function of lipids reveals why they are so crucial to life:

Energy Provision: They serve as a compact source of energy, providing approximately twice the energy per gram compared to carbohydrates or proteins.

Membrane Formation: Lipids form the fundamental matrix of all cell membranes, keeping the internal environment of the cell separate from the outside.

Insulation and Protection: Stored lipids, especially in the form of adipose tissue, protect internal organs against mechanical shocks and help maintain body temperature.

Hormone Production: Several hormones (e.g., steroids such as testosterone and oestrogen) are lipid-based.

Vitamin Absorption: Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) require dietary lipids for effective absorption.

Where do the Lipids and Proteins Constituting the Cell Membrane get Synthesised?

A frequently asked question in cell biology is:

“Where do the lipids and proteins constituting the cell membrane get synthesised?”

Lipids: Most membrane lipids are synthesised in the Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER). Enzymes in the SER catalyse the formation of phospholipids, cholesterol, and other lipid molecules.

Proteins: Membrane proteins are predominantly synthesised in the Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (RER), where ribosomes are attached to the outer surface of the RER, facilitating protein assembly.

After synthesis, these membrane components are transported to their destination via vesicles, ensuring the cell membrane is continually replenished and maintained.

Classification of Lipids

There are several ways to categorise lipids based on structure, function, and chemical composition. However, a commonly accepted classification of lipids divides them into two broad groups:

Saponifiable Lipids

Non-saponifiable Lipids

Saponifiable Lipids

Contain one or more ester functional groups.

Can be hydrolysed (saponified) in the presence of a base.

Examples: Triglycerides, waxes, phospholipids, and sphingolipids.

Non-saponifiable Lipids

Do not contain ester bonds.

Cannot be hydrolysed (saponified) in alkaline solutions.

Examples: Steroids (e.g., cholesterol), fat-soluble vitamins.

Types of Lipids

Within the broader lipids classification, there are several types of lipids crucial to understanding their diversity and role in living organisms:

1. Simple Lipids

These are esters of fatty acids with alcohols. They include:

Fats and Oils (Triglycerides):

Comprise glycerol is linked to three fatty acids.

The human body stores excess fats and oils in adipose tissue.

Waxes:

Formed by the esterification of long-chain fatty acids with long-chain alcohols.

Provide a protective coating (e.g., on leaves, fruits, bird feathers).

2. Complex Lipids

These contain components beyond just fatty acids and alcohol.

Phospholipids:

Composed of glycerol or sphingosine, two fatty acids, and a phosphate group.

Key structural elements of cell membranes.

Glycolipids (Glycosphingolipids):

Formed by the bonding of carbohydrates with lipids.

Often found on cell surfaces, crucial for cell-cell recognition.

Sphingolipids:

Built on the amino alcohol sphingosine.

Abundant in nerve cell membranes (myelin sheath).

3. Derived (or Precursor) Lipids

These are compounds derived from simple and complex lipids.

Steroids:

Identified by their four-fused-ring structure (tetracyclic).

Cholesterol, the most common steroid in animals, is vital for membrane rigidity.

Serves as a precursor for hormones (oestrogen, testosterone) and vitamin D.

Fatty Acids:

Serve as building blocks for many lipids.

Can be metabolised to generate ATP (energy).

Lipid-Soluble Vitamins (A, D, E, K):

Essential micronutrients that rely on dietary lipids for absorption.

Also Read: Hormones

Unique Insights: Beyond the Basics

To make our study of lipids more comprehensive, here are some additional points that highlight their complexity and importance:

Essential vs. Non-essential Fatty Acids

Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs), like omega-3 and omega-6, must be obtained through the diet because the human body cannot synthesise them.

Non-essential Fatty Acids can be synthesised internally.

Role in Cell Signalling

Certain lipids act as signalling molecules. Prostaglandins, for instance, are involved in processes such as inflammation and platelet aggregation.

Lipoproteins in Lipid Transport

Since lipids are insoluble in blood, they are transported as lipoproteins (e.g., LDL, HDL, VLDL). Imbalances can lead to cardiovascular issues.

HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) is often called “good cholesterol,” whereas LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein) is frequently referred to as “bad cholesterol.”

Beta-Oxidation of Fatty Acids

Fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation in the mitochondria, producing acetyl-CoA, which then enters the Krebs cycle for ATP generation. This is a key metabolic pathway in energy production.

Technological and Industrial Uses

Lipids such as vegetable oils, waxes, and cholesterol derivatives are widely used in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and the food industry.

Phospholipids are also utilised in drug delivery systems (e.g., liposomes) to improve the solubility of certain medications.

Recap: Key Points on Lipids

Lipids definition and lipids meaning: Organic compounds, insoluble in water but soluble in non-polar solvents.

What are lipids: They include fats, oils, waxes, steroids, and phospholipids, crucial for energy storage, insulation, membrane structure, and hormone production.

Structure of lipids (Lipids structure): Many feature fatty acids, glycerol, or ring structures (like steroids). The “head-and-tail” arrangement in phospholipids is key to cell membranes.

Function of lipids: Energy provision, membrane structure, hormone synthesis, insulation, and vitamin absorption.

Classification of lipids (Lipids classification): Primarily split into saponifiable (e.g., triglycerides, phospholipids) and non-saponifiable (e.g., steroids).

Types of lipids: Simple (fats, waxes), complex (phospholipids, sphingolipids, glycolipids), and derived (fatty acids, steroids).

Where do the lipids and proteins constituting the cell membrane get synthesised? Lipids are mainly produced in the Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum, while membrane proteins are formed in the Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum.

Explore More:

FAQs on Lipids: Types, Structure, Functions & Synthesis Explained

1. What are lipids and why are they considered biomolecules?

Lipids are a diverse group of organic molecules primarily composed of carbon and hydrogen atoms, making them largely non-polar and insoluble in water. They are classified as biomolecules because they are essential for life, performing critical roles in energy storage, forming structural components of cell membranes, and acting as signalling molecules. For more details, you can explore the topic of biomolecules.

2. How are lipids broadly classified? Give examples.

Lipids are broadly classified into three main groups based on their structure and composition:

- Simple Lipids: These are esters of fatty acids with various alcohols. Examples include fats, oils (triglycerides), and waxes.

- Compound Lipids: These are esters of fatty acids containing other groups in addition to an alcohol and a fatty acid. Examples include phospholipids (in cell membranes) and glycolipids.

- Derived Lipids: These are substances derived from the hydrolysis of simple and compound lipids. Examples include fatty acids, cholesterol, and steroid hormones.

3. What are the primary functions of lipids in a living organism?

Lipids perform several vital functions in the body:

- Energy Storage: They serve as a major long-term energy reserve, storing more energy per gram than carbohydrates.

- Structural Component: Phospholipids and cholesterol are fundamental components of the cell membrane, maintaining its structure and fluidity.

- Insulation and Protection: Fat stored under the skin provides thermal insulation, while fat surrounding organs acts as a protective cushion.

- Hormone Production: Steroid hormones like estrogen and testosterone are derived from cholesterol.

- Vitamin Absorption: They aid in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K).

4. Why are lipids insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents?

This property is due to their molecular structure. Lipids consist of long hydrocarbon chains that are non-polar. Water is a polar molecule. According to the principle "like dissolves like," polar substances dissolve in polar solvents, and non-polar substances dissolve in non-polar solvents. Since lipids are non-polar, they cannot form significant attractions with polar water molecules, making them insoluble. However, they readily dissolve in non-polar organic solvents like chloroform and ether.

5. How do saturated and unsaturated fats differ in their chemical structure and physical properties?

The primary difference lies in the bonds within their fatty acid chains. Saturated fats have only single bonds between carbon atoms, allowing the chains to be straight and pack closely together, making them solid at room temperature (e.g., butter). Unsaturated fats have one or more double bonds, which create kinks in the chains. These kinks prevent the molecules from packing tightly, making them liquid at room temperature (e.g., olive oil). You can learn more about the difference between saturated and unsaturated fats to understand their health implications.

6. What is the specific role of phospholipids in forming the cell membrane?

Phospholipids are amphipathic, meaning they have a polar, hydrophilic (water-attracting) head and two non-polar, hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails. In an aqueous environment, they spontaneously arrange themselves into a lipid bilayer, with the hydrophobic tails facing inward, away from the water, and the hydrophilic heads facing outward. This bilayer forms the basic framework of the cell membrane, creating a stable barrier between the cell's interior and its external environment.

7. How are lipids like cholesterol transported in the blood if they are insoluble?

Because lipids are insoluble in blood (which is mostly water), they are transported inside special particles called lipoproteins. A lipoprotein has a core of cholesterol and triglycerides, surrounded by a shell of phospholipids and proteins. This structure makes the entire particle water-soluble, allowing it to move through the bloodstream. Major types include Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) and High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL).

8. Why is cholesterol considered both essential for the body and a risk factor for disease?

Cholesterol is essential because it is a vital component of cell membranes, helping to regulate their fluidity. It is also the precursor for synthesising steroid hormones, vitamin D, and bile acids. However, it becomes a risk factor when levels of Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL), often called "bad cholesterol," are too high. Excess LDL can deposit in the walls of arteries, leading to the formation of plaque (atherosclerosis), which increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes.