How Antigen-Antibody Reactions Impact Immunity and Diagnosis

Antigen-antibody reaction is a fundamental process of the immune system in which specific proteins called antibodies bind to foreign substances termed antigens. This reaction protects our bodies by either neutralising or eliminating harmful agents such as viruses, bacteria, and toxins. In antigen-antibody reactions in microbiology, these interactions are widely used for diagnostic tests and research. Below, we will explore the detailed mechanism, properties, and antigen-antibody reaction types, along with unique insights and examples.

What is an Antigen?

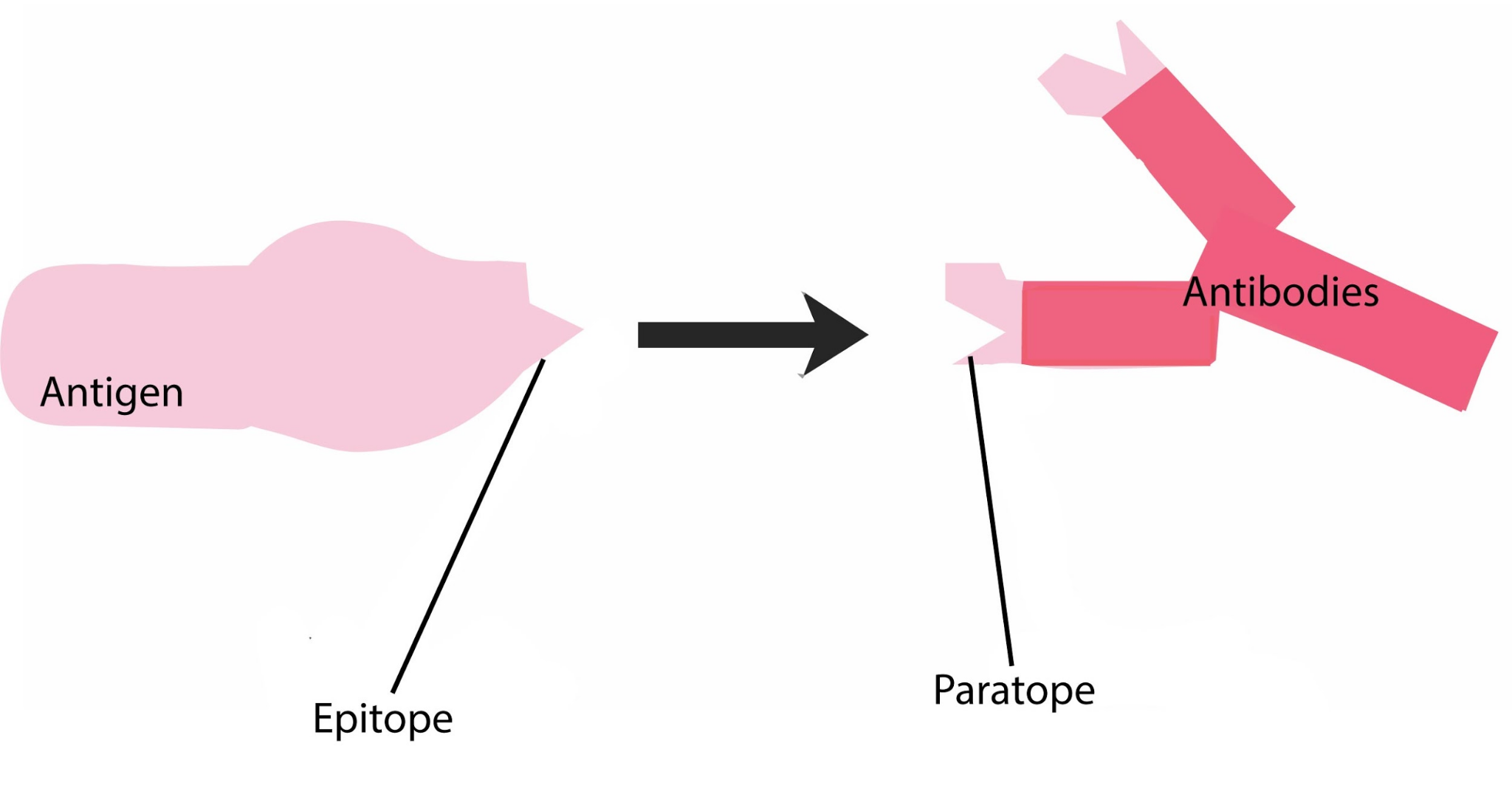

An antigen is any substance (usually foreign to the body) that triggers an immune response. It can be a protein, polysaccharide, lipid, or other molecule capable of being recognised by the immune system. A specific region on the antigen to which an antibody binds is called the epitope.

Key Points

Antigens can be immunogens (capable of eliciting an immune response on their own) or haptens (require a carrier molecule to trigger an immune response).

Common antigenic components include viral coats, bacterial cell walls, toxins, and surface proteins.

Autoantigens are the body’s components, sometimes mistakenly targeted by the immune system (as seen in autoimmune disorders).

What is an Antibody?

An antibody (also called immunoglobulin) is a Y-shaped glycoprotein produced by specialised white blood cells known as B lymphocytes (or B-cells). These antibodies specifically recognise and bind to antigens.

Key Points

Five major classes: IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE, and IgD (a quick mnemonic is “GAMED”).

Each antibody has a unique paratope, which binds to the epitope of an antigen.

Primarily generated by activated B-cells (plasma cells).

Antigen-Antibody Reaction Mechanism

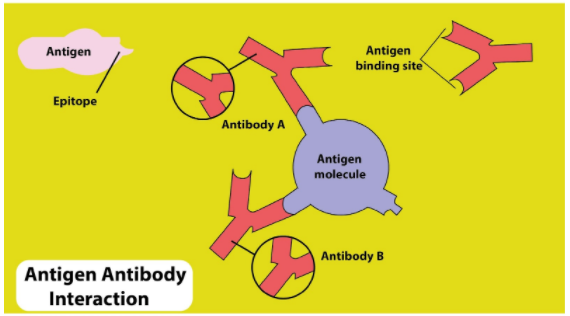

Antigen-antibody reaction is also known as the Ag-Ab reaction or serological reaction. It follows a three-stage mechanism:

Formation of the Ag-Ab Complex:

The antigen fits into the antibody’s binding site much like a key in a lock.

This step is highly specific and depends on the precise molecular structure of both antigen and antibody.

Visible Manifestation:

After binding, certain reactions become visibly apparent such as precipitation, agglutination, or colour change (in assays like ELISA).

Elimination or Neutralisation of the Antigen:

The antigen is then neutralised, lysed, or removed by various immune processes (e.g., phagocytosis).

Properties of Antigen-Antibody Reaction

Specificity: Each antibody binds only with the antigen that matches its paratope.

Reversibility: The bonds are non-covalent (e.g., ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions).

Affinity: Strength of binding between a single epitope and a paratope.

Avidity: Overall strength of binding when an antibody with multiple binding sites interacts with an antigen with multiple epitopes.

Cross-Reactivity: An antibody may bind to antigens with similar epitopes.

Types of Antigen-Antibody Reaction

When you study antigen-antibody reaction notes, you will frequently encounter these antigen-antibody reaction types:

Precipitation Reaction

Occurs when a soluble antigen combines with its specific antibody in the presence of electrolytes at an optimal pH and temperature, forming an insoluble precipitate.

Liquid Precipitation: Varying amounts of antigen are added to a fixed amount of antibody to see where visible precipitate forms.

Gel Precipitation: Antigen and antibody diffuse in a gel medium (like agar), forming precipitation lines where they meet in optimal proportions.

Agglutination Reaction

Involves the clumping (agglutination) of particulate antigens (e.g., RBCs, bacterial cells) by their specific antibodies.

Slide Agglutination: Quick test to check for agglutinating antibodies.

Tube Agglutination: Used to determine antibody titre by serial dilution.

Passive Agglutination: Converts a precipitation reaction into an agglutination reaction by coating soluble antigens onto carrier particles such as latex beads or RBCs.

Antigen-antibody reaction example here is the Widal test for diagnosing typhoid fever.

Complement Fixation

The complement system (a group of proteins) is activated when an antigen-antibody complex forms, leading to lysis of cells or microbes.

Principle: If the antibody is present, it binds the antigen and “fixes” the complement, preventing it from lysing indicator RBCs used in the test.

Immunofluorescence

Antibodies are labelled with fluorescent dyes (e.g., fluorescein) that emit visible light upon exposure to UV light.

Useful for locating or identifying antigens in cells or tissues under a fluorescence microscope.

ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay)

Detects and measures antibodies or antigens in a sample using enzyme-linked markers.

Indirect ELISA: Often used to detect antibodies (e.g., in HIV testing).

Sandwich ELISA: Detects an antigen in a sample by “sandwiching” it between two specific antibodies.

Competitive ELISA: Measures antigen concentration by observing competition between labelled and unlabelled antigens for binding sites on the antibody.

Also Read: ELISA

Antigen-Antibody Reaction in Microbiology

In microbiology, these reactions are crucial for diagnosing infectious diseases. Examples include:

Widal Test: Detects antibodies against Salmonella typhi.

VDRL Test: Used for syphilis detection.

ASO Test: Detects antibodies against Streptococcal bacteria.

These tests highlight how antigen-antibody reaction in microbiology helps identify specific infections quickly and accurately.

Mnemonic for Immunoglobulin Classes

A quick mnemonic to remember the five major antibody (immunoglobulin) classes is GAMED:

G – IgG

A – IgA

M – IgM

E – IgE

D – IgD

Quick Quiz (with Answers)

Which of the following immunoglobulins is the most abundant in human serum?

a) IgM

b) IgG

c) IgA

d) IgEAnswer: b) IgG

What is the specific name of the region on an antigen that binds to an antibody?

a) Paratope

b) Hapten

c) Epitope

d) None of the aboveAnswer: c) Epitope

Which of the following techniques uses enzymes attached to the antibody for detection?

a) Western Blot

b) ELISA

c) Immunofluorescence

d) Complement FixationAnswer: b) ELISA

Antigen-antibody reaction is also known as…

a) Immuno-coagulation

b) Serological reaction

c) Haemolysis

d) Complement cascadeAnswer: b) Serological reaction

Key Takeaways

Antigens are foreign substances that prompt an immune response, while antibodies are specialised proteins that bind to these antigens.

The antigen-antibody reaction involves a three-step process: formation of the complex, visible manifestation (e.g., agglutination), and elimination or neutralisation.

Important antigen-antibody reaction types include precipitation, agglutination, complement fixation, immunofluorescence, and ELISA.

These reactions are pivotal in diagnostic tests in antigen-antibody reactions in microbiology and play a major role in protecting the body against pathogens.

Related Topics

FAQs on Antigen-Antibody Reaction Types Explained with Examples

1. What is an antigen-antibody reaction and why is it important in the human body?

An antigen-antibody reaction is a specific chemical interaction between antibodies produced by B-cells of the immune system and antigens. An antigen is any substance that triggers an immune response, while an antibody is a protein produced to neutralise it. This reaction is fundamentally important because it is the primary way the body identifies and tags foreign invaders like bacteria and viruses for destruction, forming the basis of the adaptive immune system.

2. What are the major types of antigen-antibody reactions with examples?

The major types of antigen-antibody reactions are distinguished by the nature of the antigen and the mechanism of interaction. Key examples include:

- Precipitation: This occurs when a soluble antigen reacts with its specific antibody to form an insoluble complex called a precipitate. The VDRL test for syphilis is an example.

- Agglutination: This involves the clumping of particulate (insoluble) antigens, like bacteria or red blood cells, by antibodies. Blood typing is a classic example of an agglutination reaction.

- Neutralisation: In this reaction, antibodies bind to and block the harmful effects of toxins or the infectivity of viruses. The administration of an antitoxin for a snake bite is an example.

- Complement Fixation: This involves the activation of the complement system, a cascade of proteins that leads to the lysis (bursting) of target cells like bacteria.

3. What is the key difference between agglutination and precipitation reactions?

The key difference lies in the state of the antigen involved. A precipitation reaction occurs between an antibody and a soluble antigen, resulting in the formation of an insoluble solid (precipitate). In contrast, an agglutination reaction happens when antibodies bind to particulate or insoluble antigens, such as those on the surface of cells (like bacteria or red blood cells), causing them to clump together. You can learn more about the role of agglutinins in this process.

4. How are antigen-antibody reactions used in medical tests like ELISA?

The principle of antigen-antibody interaction is central to many diagnostic tests. In an ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay), either an antigen or an antibody is immobilised on a microplate. A patient's sample is then added. If the corresponding antibody or antigen is present in the sample, it binds to the immobilised molecule. This binding is then detected by adding an enzyme-linked antibody that causes a colour change, indicating a positive result. This method is highly sensitive and is used to detect various diseases, including HIV. Explore the full details of the ELISA test to understand its mechanism better.

5. What makes the bond between an antigen and antibody reversible?

The bond between an antigen and an antibody is reversible because it is formed by multiple non-covalent forces, not strong covalent bonds. These forces include:

- Hydrogen bonds

- Ionic bonds

- Hydrophobic interactions

- Van der Waals forces

6. How can an antibody, which is highly specific, sometimes react with the wrong antigen?

While antibodies are highly specific to a particular antigenic determinant (epitope), they can sometimes bind to a different antigen if it shares a very similar or identical epitope. This phenomenon is called cross-reactivity. It happens because the antibody's binding site (paratope) recognizes a specific shape and chemical structure. If another molecule mimics that structure, an unintended reaction can occur. This is the principle behind the cross-immunity provided by the cowpox vaccine against the smallpox virus.

7. How does the structure of an antibody, like IgG vs. IgM, affect its function in a reaction?

The structure of an antibody class directly dictates its function. For example, IgM is a large pentamer (five units joined together), giving it ten antigen-binding sites. This structure makes it extremely efficient at agglutination and activating the complement system, making it a powerful first responder in an infection. In contrast, IgG is a smaller monomer (single unit) that can easily travel through blood and tissues, and it is the only antibody class that can cross the placenta to protect a fetus. The difference between IgG and IgM is crucial in determining the stage and nature of an immune response.

8. Does an antigen-antibody reaction always destroy the pathogen directly?

No, an antigen-antibody reaction does not always lead to the direct destruction of a pathogen. While some reactions, like complement fixation, do result in cell lysis, many others function by simply 'tagging' the pathogen. Key non-destructive functions include:

- Opsonisation: Antibodies coat the pathogen, making it easier for phagocytic cells like macrophages to identify and engulf it.

- Neutralisation: Antibodies bind to toxins or viral surfaces, physically blocking them from harming or infecting host cells without destroying them.

9. What happens during an incompatible blood transfusion in terms of an antigen-antibody reaction?

During an incompatible blood transfusion, a severe antigen-antibody reaction occurs. For instance, if a person with Type A blood (having Anti-B antibodies) receives Type B blood (having B antigens), their pre-existing Anti-B antibodies will immediately bind to the B antigens on the transfused red blood cells. This triggers a massive agglutination (clumping) of red blood cells, blocking blood vessels. It also leads to widespread hemolysis (bursting of red blood cells), releasing toxic levels of haemoglobin into the bloodstream and potentially causing kidney failure and death. This is why a blood group test is critical before any transfusion.