How to Solve Two-Dimensional Elastic Collision Problems with Formulas and Examples

Elastic collision in two dimensions is a key topic in mechanics, examining interactions between two objects moving within a plane where both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved along each independent axis. This principle forms the basis for solving many problems in physics, especially in JEE Main preparation.

Definition and Characteristics of Elastic Collision in Two Dimensions

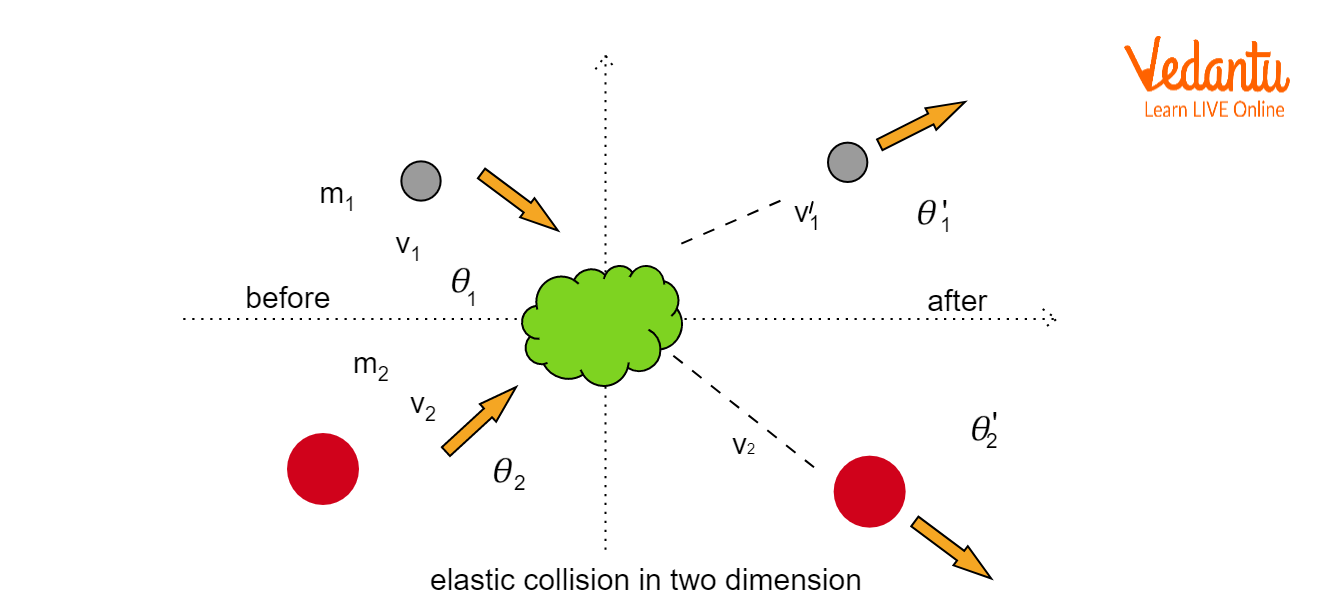

An elastic collision in two dimensions occurs when two bodies collide and both momentum and kinetic energy remain constant before and after impact. Velocities after collision are generally at arbitrary angles, requiring a vector approach for analysis.

In two-dimensional collisions, each body's velocity is resolved into x and y components. Conservation principles must be applied separately along both directions for accurate calculation.

The analysis of such collisions is fundamental in mechanics and is extensively covered in topics like the Basics of Mechanics.

Conservation Laws Governing Elastic Collisions in Two Dimensions

Elastic collisions in two dimensions always conserve total linear momentum independently along both x and y axes, as well as the total kinetic energy of the system. These laws form the basis for all equations and derivations used in analysis.

The momentum conservation equations for masses $m_1$ and $m_2$, with initial velocities $u_1$, $u_2$, and final velocities $v_1$, $v_2$ (all as vectors), are:

X-direction: $m_1 u_{1x} + m_2 u_{2x} = m_1 v_{1x} + m_2 v_{2x}$

Y-direction: $m_1 u_{1y} + m_2 u_{2y} = m_1 v_{1y} + m_2 v_{2y}$

The conservation of kinetic energy is written as:

$\dfrac{1}{2} m_1 u_1^2 + \dfrac{1}{2} m_2 u_2^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} m_1 v_1^2 + \dfrac{1}{2} m_2 v_2^2$

Effective use of these equations requires clear resolution of all velocities into components and careful attention to the direction of motion. Additional reading on momentum can be found at Momentum in Physics.

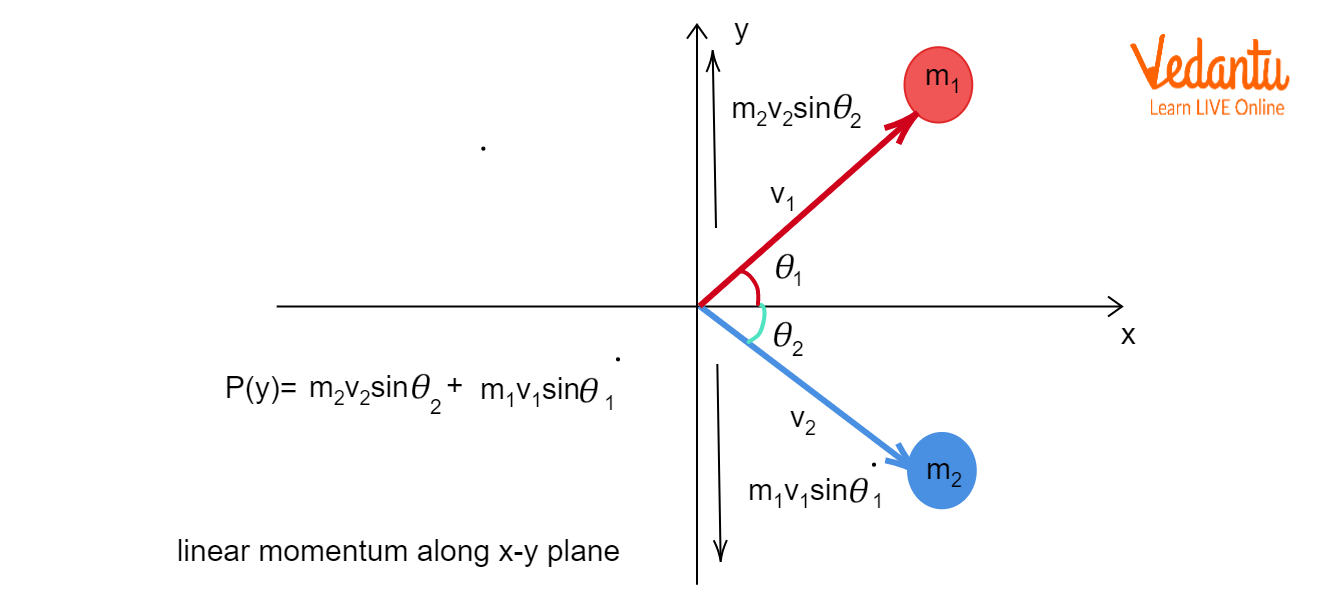

Vector Resolution and Diagrammatic Representation

To analyze an elastic collision in two dimensions, represent initial and final velocity vectors on a diagram, showing their components on the x and y axes. Directions must be established clearly for both before and after collision states.

For calculation, decompose each velocity into x and y components using trigonometric functions. For example, velocity $v$ at angle $\theta$ is split as $v_x = v\cos\theta$, $v_y = v\sin\theta$.

Applying this approach is critical in both abstract problems and practical scenarios involving Understanding Collision Types.

Stepwise Derivation: Elastic Collision in Two Dimensions

Consider two bodies with masses $m_1$ (moving with velocity $u_1$) and $m_2$ (at rest for simplicity). After collision, let $v_1$ and $v_2$ be their speeds at angles $\phi_1$ and $\phi_2$ relative to x-axis, respectively.

The x and y component equations for momentum are:

$m_1 u_1 = m_1 v_1 \cos\phi_1 + m_2 v_2 \cos\phi_2$

$0 = m_1 v_1 \sin\phi_1 - m_2 v_2 \sin\phi_2$

The kinetic energy equation simplifies (since $m_2$ is at rest) to:

$m_1 u_1^2 = m_1 v_1^2 + m_2 v_2^2$

Solving these three equations allows determination of unknown speeds and directions post-collision. The simultaneous equations often require substitution and trigonometric manipulation.

Special Cases and Notable Results

A prominent special case is when $m_1 = m_2$ and $m_2$ is initially at rest. The bodies move at right angles after a perfectly elastic collision. This feature is repeatedly used in competitive examinations.

Another case is the head-on collision, where only the x-axis needs to be considered. In glancing or oblique collisions, careful angle and sign conventions are imperative.

The key differences between elastic and inelastic collisions are summarized below.

| Collision Type | Conserved Quantity |

|---|---|

| Elastic | Momentum & Kinetic Energy |

| Inelastic | Momentum Only |

Further applications and differences can be cross-referenced in Conservation of Momentum.

Solved Example: Typical JEE Two-Dimensional Elastic Collision

Given: $m_1 = 1$ kg, $u_1 = 4$ m/s (along x-axis), $m_2 = 1$ kg initially at rest. After collision, $m_1$ moves with $v_1 = 2$ m/s at $60^\circ$ from x-axis.

Find: $m_2$'s speed $v_2$ and angle $\theta$ (from x-axis).

Step 1: Momentum in x: $4 = 2 \cos 60^\circ + v_2 \cos\theta$

$4 = 1 + v_2 \cos\theta$

Step 2: Momentum in y: $0 = 2 \sin 60^\circ - v_2 \sin\theta$

$v_2 \sin\theta = 2 \times 0.866 = 1.732$

Step 3: $v_2^2 = (3)^2 + (1.732)^2 = 9 + 3 = 12,$ so $v_2 = 3.46$ m/s. $\cos\theta = 3/3.46$

Such examples reinforce the importance of resolving each velocity into components and applying conservation principles systematically. Application of energy concepts is detailed at Concept of Energy.

Differences Between Elastic and Inelastic Collisions in Two Dimensions

In elastic collisions, both kinetic energy and momentum are conserved. In inelastic collisions, only momentum is conserved while kinetic energy decreases due to conversion into heat, sound, or deformation.

Perfectly inelastic collisions occur when bodies stick together after collision, resulting in maximum kinetic energy loss allowed by conservation of momentum.

The coefficient of restitution $(e)$ distinguishes elastic from inelastic collisions: $e = 1$ for elastic, $0 < e < 1$ for inelastic scenarios.

Important Tips and Practice Guidelines for JEE

Always resolve the velocities for each mass before and after collision into perpendicular axes. Component form reduces error and clarifies directionality in all calculations.

Check that sign conventions are consistent across axes. Incorrect assignment often leads to errors in both theory and numerical solutions.

- Conserve momentum along each axis separately

- Conserve kinetic energy if and only if collision is elastic

- Apply trigonometric resolution for all velocities

- Draw vector diagrams to understand direction changes

- Always check for energy loss when problem mentions inelasticity

Connections with related mechanics topics ensure robust preparation. Further conceptual insights can be enhanced by studying the Basics of Mechanics.

FAQs on Understanding Elastic Collisions in Two Dimensions

1. What is an elastic collision in two dimensions?

An elastic collision in two dimensions is a type of collision in which both kinetic energy and momentum are conserved. In this type of collision:

- Kinetic energy is not lost to heat, sound, or deformation.

- Total momentum before and after the collision remains the same in both x and y directions.

- Examples include the collision of billiard balls or air-hockey pucks.

2. State the conditions necessary for a collision to be considered elastic.

For a collision to be considered elastic:

- Total kinetic energy of the system is conserved.

- Total momentum of the system is conserved in all directions.

- No energy is lost due to deformation, friction, or sound.

3. How do you solve elastic collision problems in two dimensions?

To solve elastic collision problems in two dimensions, use conservation laws:

- Write equations for momentum conservation in both x and y directions.

- Write the equation for kinetic energy conservation.

- Solve the system of equations to find final velocities and directions of the objects involved.

4. Give examples of elastic collisions in daily life.

Common examples of elastic collisions in daily life include:

- Billiard balls colliding on a pool table.

- Air hockey pucks hitting each other.

- Molecules colliding in the air (ideal gas assumption).

5. Write the equations for conservation of momentum in a two-dimensional elastic collision.

In a two-dimensional elastic collision, the conservation of momentum is applied separately to both axes:

- In the x-direction: m₁u₁x + m₂u₂x = m₁v₁x + m₂v₂x

- In the y-direction: m₁u₁y + m₂u₂y = m₁v₁y + m₂v₂y

- Here, u represents initial velocity, v represents final velocity, and m is mass.

6. What are the key differences between elastic and inelastic collisions?

The main differences between elastic and inelastic collisions are:

- Elastic collisions conserve both momentum and kinetic energy.

- Inelastic collisions conserve only momentum; kinetic energy is not conserved.

- Objects may stick together after inelastic collisions, but remain separate in elastic ones.

7. Why is kinetic energy conserved in elastic collisions?

Kinetic energy is conserved in elastic collisions because no energy is lost to other forms like heat, sound, or deformation. This means all the mechanical energy remains within the system as kinetic energy before and after the collision.

8. What happens to the velocity of two equal masses after a perfectly elastic head-on collision?

In a perfectly elastic head-on collision between two equal masses, the velocities are exchanged after the collision. This means:

- The first mass moves with the initial velocity of the second mass.

- The second mass moves with the initial velocity of the first mass.

9. Can you derive the final velocities of two objects after a two-dimensional elastic collision?

Yes, the final velocities in a two-dimensional elastic collision can be derived using:

- Momentum conservation equations in both x and y directions.

- Kinetic energy conservation equation.

- Solving these simultaneous equations gives the final velocities and angles for both objects.

10. Is momentum always conserved in a two-dimensional collision? Explain.

Yes, total momentum is always conserved in a two-dimensional collision, provided no external force acts on the system. This applies to both elastic and inelastic collisions and in both the x and y directions.

11. What is the formula for kinetic energy conservation in elastic collisions?

The formula for kinetic energy conservation in elastic collisions is:

Total kinetic energy before collision = Total kinetic energy after collision

Mathematically, ½m₁u₁² + ½m₂u₂² = ½m₁v₁² + ½m₂v₂²

12. In a two-dimensional elastic collision, why must both x and y components of momentum be considered?

Both x and y components of momentum must be considered because the objects can move in any direction within the plane. This ensures accurate calculation of the final velocities and directions after the collision.