How to Solve Coordinate Geometry Problems with Simple Examples

Coordinate Geometry is a foundational branch of mathematics that merges geometric concepts with algebraic techniques for studying and analyzing the positions and properties of figures in a coordinate plane. Mastery of this topic is essential for excelling in competitive examinations such as JEE Main, since it equips students to solve problems involving lines, curves, and loci using precise analytic tools.

The Cartesian Coordinate System

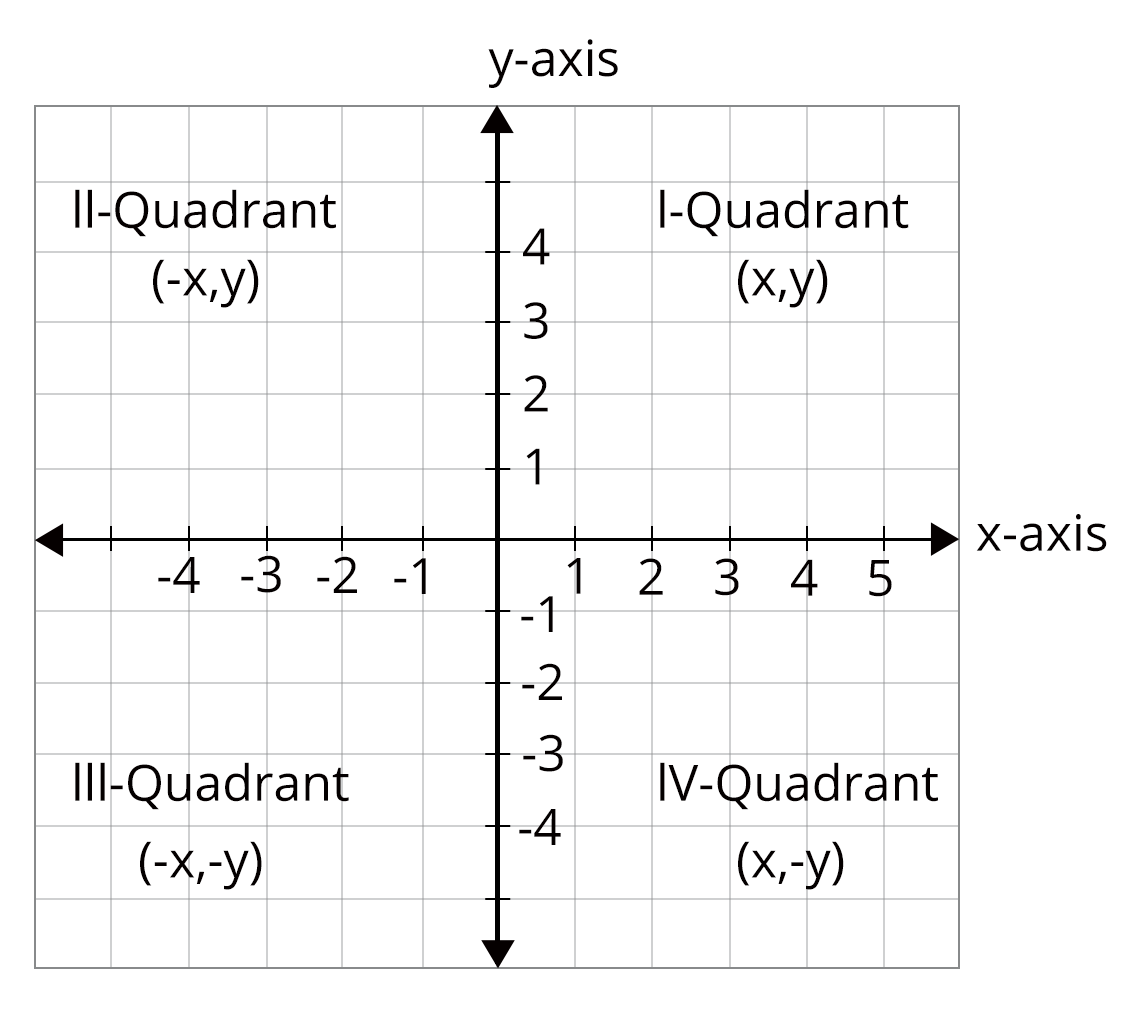

The Cartesian coordinate system is constructed by two mutually perpendicular axes: the horizontal x-axis and the vertical y-axis. Their intersection point, termed the origin, is denoted by (0, 0). Each point in the plane is represented uniquely as an ordered pair (x, y), where x is the abscissa and y is the ordinate.

The axes divide the plane into four distinct quadrants. The sign of the coordinates determines the quadrant in which the point lies. Positive abscissa and ordinate indicate the first quadrant, while other combinations correspond to subsequent quadrants as defined by the sign conventions.

Fundamental Concepts and Formulas

Coordinate geometry provides algebraic formulas that allow the computation of essential geometric properties in the plane. These formulas underpin further developments and problem-solving strategies in advanced mathematics.

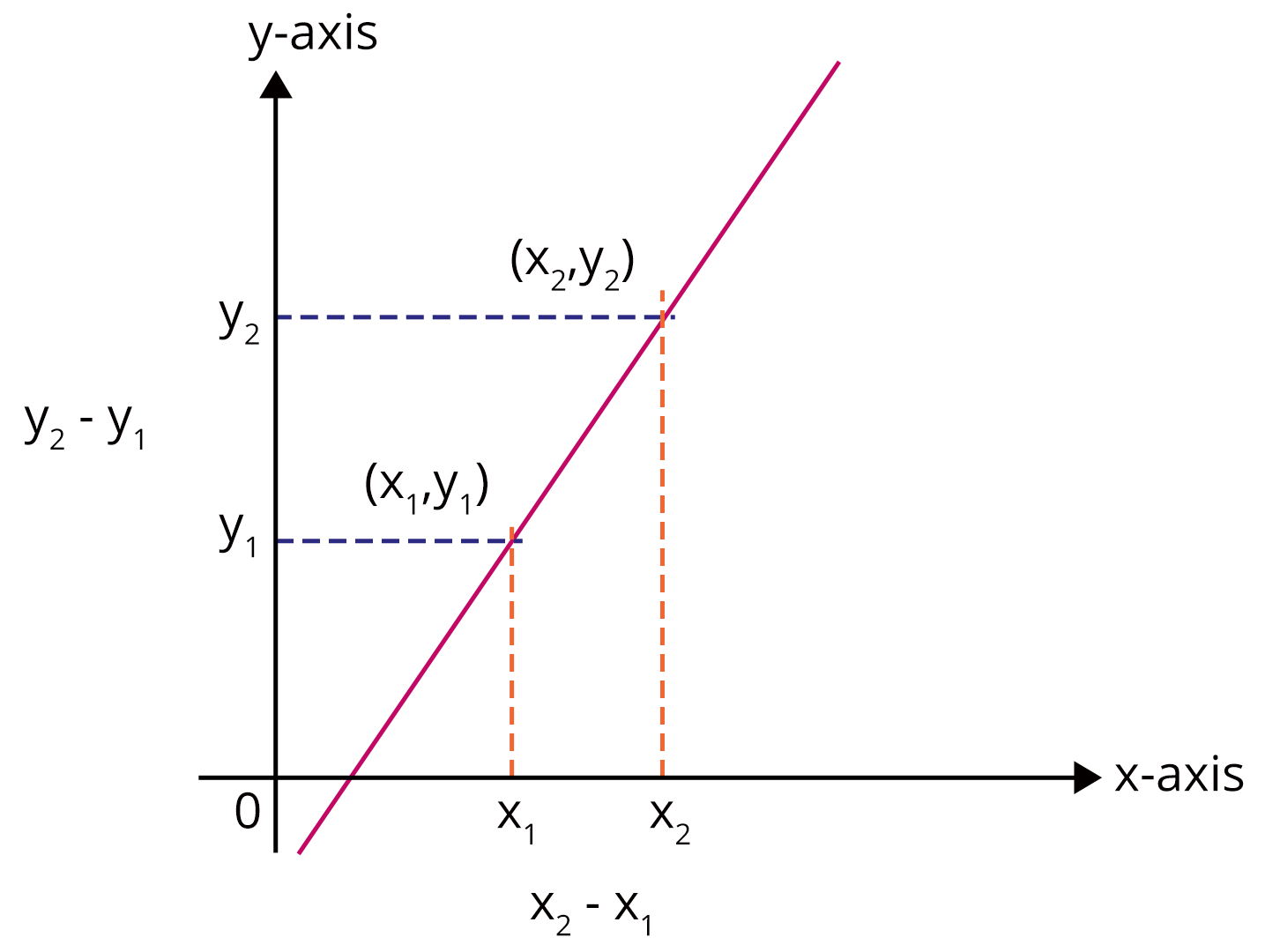

1. Distance Formula: Given two points \(A(x_1, y_1)\) and \(B(x_2, y_2)\), the distance between them is calculated by:

\[ d = \sqrt{(x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2} \]

This follows directly from the Pythagorean Theorem, considering the changes in x and y as legs of a right triangle.

2. Section Formula: If a point divides the segment from \(A(x_1, y_1)\) to \(B(x_2, y_2)\) in the ratio \(m:n\), the coordinates of the point \(P\) are:

\[ (x, y) = \left( \dfrac{mx_2 + nx_1}{m + n},\, \dfrac{my_2 + ny_1}{m + n} \right) \]

3. Midpoint Formula: The midpoint \(M\) of the segment joining \(A(x_1, y_1)\) and \(B(x_2, y_2)\) is given by:

\[ M = \left( \dfrac{x_1 + x_2}{2},\, \dfrac{y_1 + y_2}{2} \right) \]

4. Slope of a Line: The slope \(m\) of the line passing through \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\) is:

\[ m = \dfrac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1} \]

5. Area of a Triangle: For vertices \(A(x_1, y_1)\), \(B(x_2, y_2)\), and \(C(x_3, y_3)\), the area is computed by:

\[ \text{Area} = \dfrac{1}{2}\left| x_1(y_2 - y_3) + x_2(y_3 - y_1) + x_3(y_1 - y_2) \right| \]

These formulas are foundational; their correct application allows the analysis of geometric loci, properties of figures, and the solution of numerous coordinate geometry problems. For a comprehensive catalogue, review the Coordinate Geometry Overview.

Equation of a Straight Line

The general equation of a straight line in two-dimensional space is:

\[ ax + by + c = 0 \]

This can be converted to many standard forms to suit given information or problem constraints.

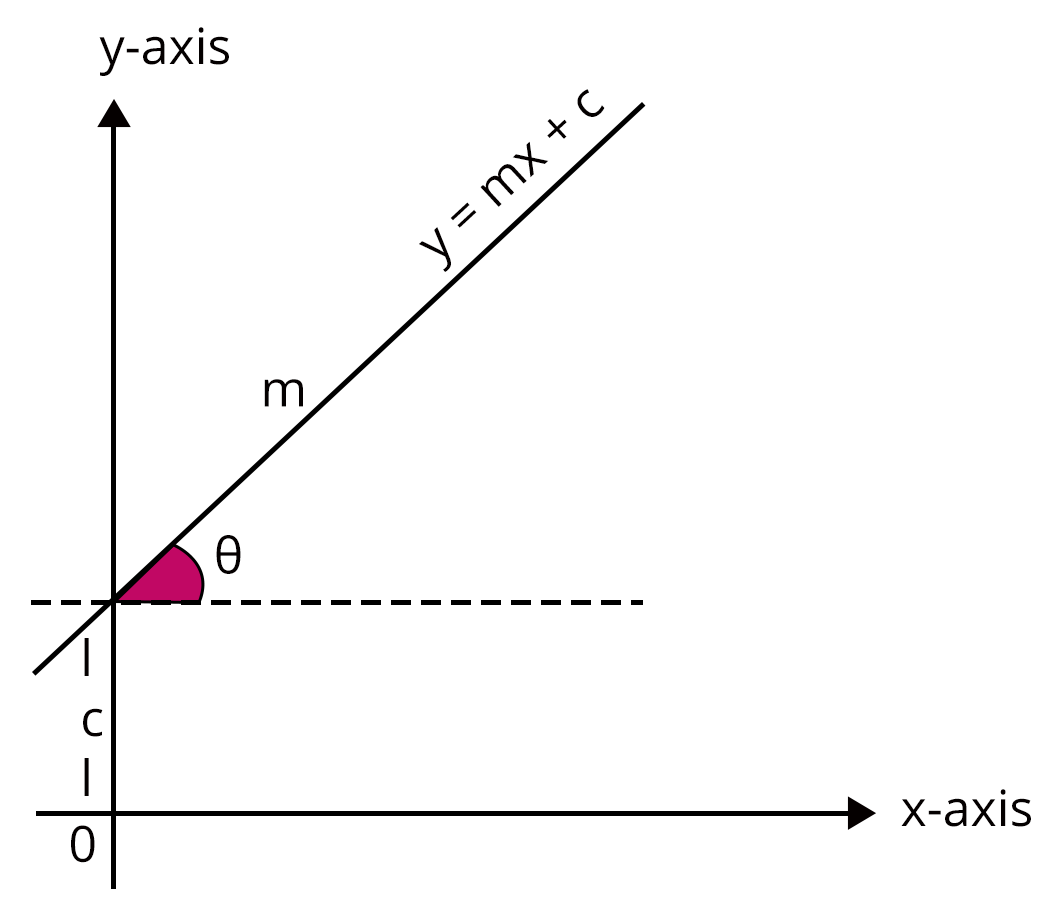

Slope–Intercept Form:

\[ y = mx + c \]

where \(m\) is the slope of the line and \(c\) is the y-intercept.

Point–Slope Form:

\[ y - y_1 = m(x - x_1) \]

where \((x_1, y_1)\) is a point on the line and \(m\) is its slope.

Two-Point Form:

\[ y - y_1 = \dfrac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}(x - x_1) \]

Intercept Form:

\[ \dfrac{x}{a} + \dfrac{y}{b} = 1 \] where \(a\) and \(b\) are the x- and y-intercepts respectively.

The normal form and other forms also arise in advanced contexts. Algebraic manipulation of these equations assists in deducing properties such as parallelism, perpendicularity, and distance from a point to a line—topics detailed in Distance Between Two Parallel Lines.

Collinearity and Locus in Coordinate Geometry

Three or more points are said to be collinear if they lie on the same straight line. Analytically, for points \(A(x_1, y_1)\), \(B(x_2, y_2)\), and \(C(x_3, y_3)\), collinearity is established when:

\[ \dfrac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1} = \dfrac{y_3 - y_2}{x_3 - x_2} \]

Alternatively, if the area formula for the triangle they form equals zero, the points are collinear.

The concept of locus is central to coordinate geometry. A locus is the set of all points satisfying specified algebraic or geometric conditions. For example, the collection of all points equidistant from a fixed point—the definition of a circle—yields the locus:

\[ (x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2 = r^2 \]

Centroid and Advanced Points

If three vertices of a triangle are \(A(x_1, y_1)\), \(B(x_2, y_2)\), and \(C(x_3, y_3)\), the centroid \(G\), where the medians intersect, has coordinates:

\[ G = \left(\dfrac{x_1 + x_2 + x_3}{3},\, \dfrac{y_1 + y_2 + y_3}{3} \right) \]

Other points of concurrency such as the circumcentre, incenter, and orthocentre also have coordinate formulas derived by geometric conditions, and can be addressed in higher-level problems.

Conic Sections in Coordinate Geometry

Conic sections arise from the intersection of a plane with a double-napped cone, leading to structures such as circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas—all central to coordinate geometry and the JEE syllabus.

Circle: The standard equation for a circle with centre \((h, k)\) and radius \(r\) is:

\[ (x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2 = r^2 \]

Ellipse: For an ellipse with centre \((h, k)\), semi-axes \(a, b\):

\[ \dfrac{(x - h)^2}{a^2} + \dfrac{(y - k)^2}{b^2} = 1 \]

Parabola: For a parabola opening rightwards with vertex at \((h, k)\):

\[ (y - k)^2 = 4p(x - h) \]

Hyperbola:

\[ \dfrac{(x - h)^2}{a^2} - \dfrac{(y - k)^2}{b^2} = 1 \]

The general second degree equation \(Ax^2 + Bxy + Cy^2 + Dx + Ey + F = 0\) represents all conic sections, including degenerate cases. Eccentricity, denoted by \(e\), measures deviation from circularity. For a circle \(e = 0\); ellipse \(0 < e < 1\); parabola \(e = 1\); hyperbola \(e > 1\). For more, refer to Family of Circles.

Key Solved Examples

Application of coordinate geometry demands familiarity with stepwise problem solving. The following solved examples illustrate the standard methods employed at the JEE Main level.

Example 1: The midpoint of the line segment joining \(A(-9, -4)\) and \(B(5, 6)\) is given as \((-2, 1)\). Find the coordinates of \(A\), when \(B\) and the midpoint are known.

Set \((x_1, y_1)\) as unknown coordinates and apply the midpoint formula:

\((x, y) = \left( \dfrac{x_1 + 5}{2},\, \dfrac{y_1 + 6}{2} \right ) = (-2, 1)\)

Solving: \[ \dfrac{x_1 + 5}{2} = -2 \implies x_1 = -9,\;\; \dfrac{y_1 + 6}{2} = 1 \implies y_1 = -4 \]

Thus, \(A = (-9, -4)\).

Example 2: Find the equation of the line through \((-2, 3)\) with slope \(-1\).

Point-slope form yields:

\(y - 3 = -1(x + 2)\), hence \(x + y = 1\).

Example 3: Find the equation of a line with slope \(-2\) and y-intercept \(1\).

In slope-intercept form: \(y = -2x + 1\), or \(2x + y = 1\).

Special Results and Further Applications

Coordinate geometry also addresses the calculation of angles between lines, the distance from a point to a line, and other advanced constructs. For example, the angle \(\theta\) between lines \(L_1: a_1x + b_1y + c_1 = 0\), \(L_2: a_2x + b_2y + c_2 = 0\) is:

\[ \tan\theta = \left| \dfrac{a_1b_2 - a_2b_1}{a_1a_2 + b_1b_2} \right| \]

The perpendicular distance from \(P(x_1, y_1)\) to \(ax + by + c = 0\) is:

\[ d = \dfrac{|ax_1 + by_1 + c|}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2}} \]

These tools enable students to analyze intersections, projections, and geometric relations in the plane. For more formulas and applications, see Distance Between Two Parallel Lines.

Real-World Applications of Coordinate Geometry

Coordinate geometry is fundamental in a variety of real-world contexts, enabling precise mapping (e.g., GPS systems), the design of engineering structures, digital graphics, robotics, astronomy, and many branches of physics and economics.

Its principles are crucial for rigorous spatial analysis and are applied in both pure and applied mathematical investigations, from navigation to data modeling and beyond.

Best Practices and Common Pitfalls in Problem-Solving

Mastery of coordinate geometry is predicated on precise visualization, faultless algebraic manipulation, and thoughtful application of formulas. Errors often arise from misinterpretation of signs, incorrect substitution, or overlooking the geometric context of algebraic procedures.

- Careful diagram construction clarifies geometric relations

- Methodical double-checking prevents computational errors

- Formula memorization accelerates solution strategies

- Critical interpretation of units and constraints is essential

Students are encouraged to consult Important Questions in Coordinate Geometry for deeper practice, and to continually reinforce their skills through systematic problem-solving.

FAQs on Understanding Coordinate Geometry: Points, Lines, and Planes

1. What is coordinate geometry?

Coordinate geometry, also called Cartesian geometry, is a branch of mathematics that uses coordinates and algebraic formulas to study the positions and relationships of geometric shapes on a plane.

Key points include:

- Combines algebra with geometry.

- Uses horizontal (x-axis) and vertical (y-axis) lines to locate points.

- Helps calculate distance, area, and properties of shapes.

2. What is the formula to calculate the distance between two points in coordinate geometry?

The distance formula calculates the straight-line distance between two points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂):

- Distance = √[(x₂ − x₁)² + (y₂ − y₁)²]

- This is derived from the Pythagorean theorem.

5. What are the applications of coordinate geometry?

Coordinate geometry is widely used to solve real-world and mathematical problems involving positions and shapes, such as:

- Locating points and shapes on maps

- Calculating distances and areas

- Analyzing graphs and equations

- Solving geometry problems in exams

6. What is the difference between Cartesian and polar coordinates?

The main difference lies in how locations are represented on a plane:

- Cartesian coordinates use (x, y) axes, measuring horizontal and vertical distances.

- Polar coordinates use (r, θ) where r is the radius (distance from origin), and θ is the angle from the positive x-axis.

7. How do you prove that three points are collinear in coordinate geometry?

To prove three points are collinear (lie on a straight line), check if the area of the triangle they form is zero:

- For points A(x₁, y₁), B(x₂, y₂), C(x₃, y₃):

- Area = ½ |x₁(y₂−y₃) + x₂(y₃−y₁) + x₃(y₁−y₂)|

- If area = 0, then points are collinear.

8. What is the equation of a straight line in coordinate geometry?

The basic equation of a straight line is y = mx + c:

- m is the slope (gradient) of the line.

- c is the y-intercept (where the line crosses the y-axis).

- This form is called the slope-intercept form.

9. What are the coordinates of the origin in coordinate geometry?

The origin is the reference point where the x-axis and y-axis intersect on a coordinate plane:

- Coordinates of the origin: (0, 0)

- It serves as the starting location for plotting all other points.

10. How do you determine the slope of a line joining two points?

The slope (m) measures the steepness of a line between two points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂):

- Slope = m = (y₂ − y₁) / (x₂ − x₁)

- Positive slope means the line rises, negative slope means it falls.

11. What is the use of coordinate axes in geometry?

Coordinate axes provide a reference framework in coordinate geometry to locate points and shapes:

- The x-axis runs horizontally; the y-axis runs vertically.

- They intersect at the origin (0, 0).

- All coordinates are measured with respect to these axes.

12. What are quadrants in a coordinate plane?

A coordinate plane is divided into four quadrants by the axes:

- Quadrant I: (+, +)

- Quadrant II: (−, +)

- Quadrant III: (−, −)

- Quadrant IV: (+, −)

- This helps identify the signs of coordinates in each section.