How to Calculate Moment of Inertia for Continuous Shaped Objects

The moment of inertia of continuous bodies describes the resistance an object offers to angular acceleration about an axis, due to the distribution of its mass. For continuous mass distributions, the concept extends beyond discrete particles, requiring integration over the entire body. This topic is essential for understanding rotational dynamics at the JEE Main level.

Definition of Moment of Inertia for Continuous Bodies

For a continuous body, the moment of inertia ($I$) about a given axis is defined as the integral over its entire mass. It quantifies how mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation. The basic expression is $I = \int{r^2 \, dm}$, where $r$ is the perpendicular distance of an elemental mass $dm$ from the axis.

Moment of Inertia Formula for Continuous Mass Distribution

In the case of continuous bodies, the total moment of inertia is not a simple sum but a definite integral, expressed as $I = \int r^2 \, dm$. This integral evaluates the contribution of all infinitesimal mass elements at varying distances from the axis.

The choice of coordinate system and the axis of rotation are crucial for evaluating this integral. This general method applies to all standard and irregular bodies.

Factors Affecting Moment of Inertia of Continuous Bodies

The moment of inertia depends on the shape and size of the body, the axis selected, and the distribution of mass with respect to this axis. More mass located farther from the axis increases the moment of inertia.

- Distribution of mass relative to axis

- Shape and symmetry of the body

- Distance between mass elements and axis

Bodies with symmetrical mass arrangements, such as spheres, have lower moments of inertia compared to bodies where mass is further from the axis. The symmetry and geometric properties simplify integral calculations in standard solvable cases.

The axis of rotation plays a defining role. Changing the axis alters the values of $r$ for all mass elements, directly affecting $I$. Related topics include the Moment Of Inertia Overview.

Mathematical Representation and Calculation

For actual calculation, mass elements are expressed in terms of density and differential volume, area, or length, depending on the body’s shape. For example, in terms of density $\rho$, $dm = \rho \, dV$ for a solid body, where $dV$ is the infinitesimal volume element.

The moment of inertia of a continuous rod of length $L$ and mass $M$ about an axis through its center perpendicular to its length is $I = \dfrac{1}{12} M L^{2}$. For a solid cylinder, $I = \dfrac{1}{2} M R^{2}$ about its central axis.

Theorems Useful in Calculating Moment of Inertia

When the axis of rotation does not pass through the body’s center of mass or when dealing with planar objects, certain theorems assist in simplifying calculations. The Parallel and Perpendicular Axis Theorems are most often used in the evaluation of the moment of inertia for continuous bodies.

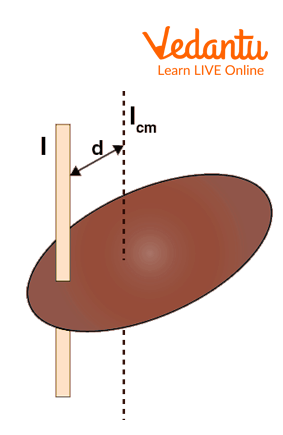

Parallel Axis Theorem

The Parallel Axis Theorem states that the moment of inertia of a body about any axis parallel to an axis passing through its center of mass equals the sum of the moment of inertia through the center of mass and the product of the body's mass and the square of the distance ($d$) between the axes:

$I = I_{cm} + M d^2$

This theorem is critical for finding the moment of inertia about axes that do not pass through the centroid of the body, as in many engineering and physics problems.

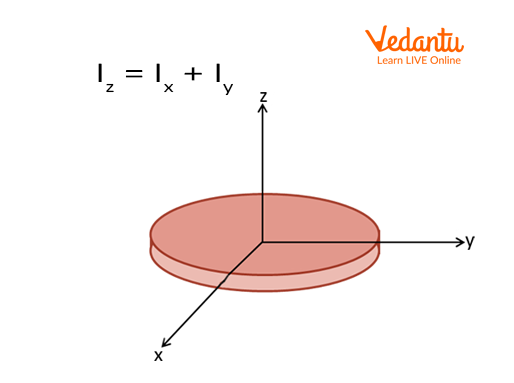

Perpendicular Axis Theorem

Applicable to planar (flat) bodies, the Perpendicular Axis Theorem states that the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the plane of the body ($I_z$) is equal to the sum of the moments of inertia about two perpendicular axes ($I_x$ and $I_y$) lying in the plane and intersecting at a point where $I_z$ passes through:

$I_z = I_x + I_y$

This theorem is especially useful for calculating the moment of inertia of flat, continuous objects like discs, plates, and rings.

Standard Moments of Inertia for Continuous Bodies

Certain standard geometries occur frequently in rotational dynamics problems. The moments of inertia for these bodies, calculated using integration and suitable coordinate systems, are summarized below for axes of symmetry.

| Body | Moment of Inertia ($I$) |

|---|---|

| Thin Rod (center axis) | $\dfrac{1}{12} M L^2$ |

| Thin Rod (end axis) | $\dfrac{1}{3} M L^2$ |

| Solid Cylinder (central axis) | $\dfrac{1}{2} M R^2$ |

| Solid Sphere (diameter) | $\dfrac{2}{5} M R^2$ |

| Hoop (central axis) | $M R^2$ |

| Rectangular Plate (about center) | $\dfrac{1}{12} M (h^2 + w^2)$ |

Other important geometries, such as discs and hollow spheres, have specific moments of inertia derivable using the base formula. Calculations for such geometries can be referred at Moment Of Inertia Of A Disc and Moment Of Inertia Of A Hollow Sphere.

Application to Non-Symmetric and Composite Bodies

For bodies lacking symmetry or composed of multiple parts, the total moment of inertia is the algebraic sum of moments of inertia of all regions about the axis. Proper selection of axes and use of theorems are essential for accurate computation.

For further reading on the continuous distribution in specific cases, concepts for circular and annular shapes are provided at Moment Of Inertia Of A Circle, Moment Of Inertia Of Annular Disc, and for triangular regions at Moment Of Inertia Of A Triangle.

Importance and Use in Rotational Dynamics

The moment of inertia is essential for determining rotational motion, angular acceleration, and the rotational analog of Newton’s second law ($\tau = I \alpha$). Knowledge of standard values simplifies analysis of rotating rigid bodies in physics and engineering contexts.

Summary Table of Key Points

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Formula | $I = \int r^2 \, dm$ |

| Depends On | Mass distribution and axis |

| Major Theorems | Parallel and Perpendicular Axis |

| Applications | Rotational motion, torque calculation |

FAQs on Understanding the Moment of Inertia for Continuous Bodies

1. What is the moment of inertia of continuous bodies?

Moment of inertia of a continuous body measures how much it resists rotational acceleration about an axis, based on its mass distribution.

- It is defined as an integral: I = ∫ r² dm, where r is the distance from the axis and dm is a mass element.

- For continuous bodies, the sum is performed using calculus over the whole volume.

- It depends on the mass, shape, and axis of rotation.

- Common continuous shapes (rod, disc, sphere) have specific formulas based on integration.

2. How is moment of inertia calculated for different shapes?

The moment of inertia for different shapes is calculated using integral calculus, applying the formula I = ∫ r² dm and considering their geometry.

- For a thin rod about its center: I = (1/12)ML²

- For a solid disc about its center: I = (1/2)MR²

- For a solid sphere about its center: I = (2/5)MR²

- For a hollow cylinder: I = MR²

These formulas come from integrating mass elements at varying distances from the chosen axis.

3. What are the factors affecting the moment of inertia of a body?

Moment of inertia depends mainly on how the mass is distributed around the rotation axis.

- Total mass (M) of the body

- Distance of each mass element from the axis (r)

- Axis of rotation position and orientation

- Shape and size of the object

Generally, the farther mass is from the axis, the greater the moment of inertia.

4. Why is moment of inertia called rotational inertia?

Moment of inertia is called rotational inertia because it quantifies a body's resistance to changes in its rotational motion, similar to how mass measures resistance to linear motion.

- Represents difficulty in changing rotational speed

- Higher moment of inertia means more torque is required for the same angular acceleration

This concept is crucial in physics and mechanics of rotation.

5. What is the physical significance of moment of inertia?

The physical significance of moment of inertia is that it determines how much a force (torque) is needed to rotate an object about an axis.

- Governs angular acceleration (Newton's 2nd law for rotation: τ = Iα)

- Influences stability in spinning objects

- Essential for designing rotating machinery, vehicles, and sports equipment

6. Write the expression for moment of inertia of a uniform rod about its center.

The moment of inertia of a uniform rod of length L and mass M about an axis passing through its center and perpendicular to its length is:

- I = (1/12)ML²

This standard result follows from integrating the mass distribution along the rod.

7. What is the difference between moment of inertia and mass?

Mass measures the amount of matter in an object and controls resistance to linear acceleration, while moment of inertia measures resistance to angular acceleration around a given axis.

- Mass: Scalar, independent of axis

- Moment of inertia: Depends on axis location and object's shape

- Both are inertia measures but for different motions (linear vs. rotational)

8. State the parallel axis theorem for moment of inertia.

The parallel axis theorem states that the moment of inertia (I) about any axis parallel to and a distance d away from the center-of-mass axis is:

- I = Icm + Md²

where Icm is the moment of inertia about the center-of-mass axis, M is total mass, and d is the perpendicular distance between the axes.

9. How does moment of inertia change if all mass is moved farther from the axis?

If all or most of a body's mass is moved farther from the rotation axis, its moment of inertia increases significantly.

- Moment of inertia is proportional to the square of distance from the axis (I ∝ r²)

- This is why flywheels and gymnasts extend arms/legs to increase inertia and slow rotation

- Design of machinery often considers this for stability and speed control

10. Explain the concept of radius of gyration.

The radius of gyration (k) is the distance from the axis at which the whole mass of a body could be concentrated without changing its moment of inertia.

- Defined by I = Mk²

- Helps compare how mass distributions affect rotational dynamics

- For calculation, k = √(I/M)