Key Principles and Formulas of Rotational Motion

Dynamics of rotational motion about a fixed axis is a fundamental area in mechanics, addressing how and why rigid bodies rotate when subject to forces and torques. This topic is crucial for understanding rotational behavior in various physical systems, and forms a major part of JEE Main physics preparations.

Rotational Motion Versus Circular Motion

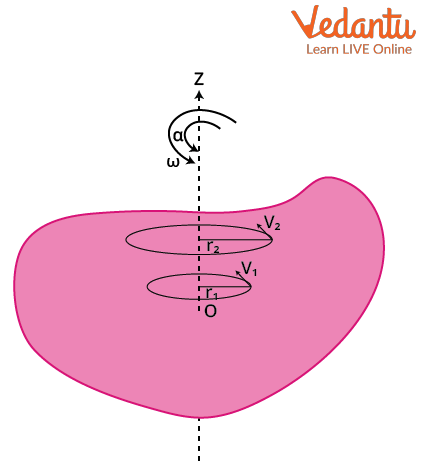

Rotational motion occurs when a rigid body turns about a fixed axis, with all its points moving in circles centered on that axis. In contrast, circular motion involves a single particle or point object tracing a circular path, not necessarily centered on an axis of rotation.

In rotational motion, each point on the body describes a circle with a radius equal to its perpendicular distance from the axis. This systematic rotation distinguishes it from general circular motion of individual particles. For detailed discussion, refer to Exploring Rotational Motion.

Fundamental Quantities in Rotational Dynamics

The primary quantities in rotational dynamics include angular displacement, angular velocity ($\omega$), angular acceleration ($\alpha$), moment of inertia ($I$), torque ($\tau$), and angular momentum ($L$).

The moment of inertia is the rotational analogue of mass and determines the resistance of a body to changes in its rotational motion. It is defined as $I = \sum_{i} m_{i} r_{i}^2$, where $m_i$ is the mass of the $i^\text{th}$ particle and $r_i$ is its perpendicular distance from the axis.

Torque is the rotational equivalent of force and is given by $\tau = r \times F$, where $F$ is the force applied at a distance $r$ from the axis. For comprehensive treatment of torque, see Torque And Rotational Motion.

Angular momentum, the rotational analogue of linear momentum, is described by $L = r \times p$ for a particle, and for a rigid body as $L = I \omega$.

Kinematics of Rotational Motion

Angular displacement ($\theta$), angular velocity ($\omega$), and angular acceleration ($\alpha$) are key descriptors of rotational kinematics. Their relationships parallel those in linear kinematics.

The relationship between linear velocity ($v$) of a particle and angular velocity is $v = r \omega$. Similarly, linear acceleration ($a$) relates to angular acceleration by $a = r \alpha$.

Dynamics of Rotation: Torque and Angular Acceleration

The rotational analogue of Newton's second law relates torque, moment of inertia, and angular acceleration. This is given by the equation $\tau = I\alpha$, where $\tau$ is the net torque, $I$ is the moment of inertia, and $\alpha$ is the angular acceleration.

This equation governs the motion of a rigid body about a fixed axis. Only the components of forces perpendicular to the radius contribute to the effective torque, leading to changes in angular velocity.

The distribution of mass, expressed through $I$, plays a vital role in rotational motion. For more on moment of inertia and its role, refer to Understanding Moment Of Inertia.

Work and Energy in Rotational Motion

The work done by torque in rotating a rigid body through an angle $\theta$ is $W = \tau \theta$ for constant torque. For a variable torque, $W = \int \vec{\tau} \cdot d\vec{\theta}$.

The rotational kinetic energy for a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis is $K = \dfrac{1}{2} I \omega^2$.

The work–energy theorem in rotation shows that the net work done by torques equals the change in rotational kinetic energy. For related concepts, visit Work, Energy, And Power.

Angular Momentum and Its Conservation

Angular momentum for rotation about a fixed axis is $L = I\omega$. In the absence of external torque, angular momentum remains conserved ($\tau_\text{ext} = 0 \implies L = \text{constant}$).

Conservation of angular momentum is a key principle in rotational motion, analogous to conservation of linear momentum in translational motion. For more detail, refer to Angular Momentum Of Rotating Body.

Key Formulas for Dynamics of Rotational Motion

- Moment of inertia: $I = \sum m_{i} r_{i}^{2}$

- Torque: $\tau = r \times F$

- Angular momentum: $L = I\omega$

- Rotational kinetic energy: $K = \dfrac{1}{2} I\omega^2$

- Newton’s second law: $\tau = I\alpha$

- Work done by torque: $W = \tau \theta$

Solved Example: Calculating Angular Acceleration

A uniform disc of mass $2$ kg and radius $0.5$ m rotates about a fixed axis. If a constant torque of $1$ Nm is applied, calculate its angular acceleration.

| Step | Calculation |

|---|---|

| Moment of inertia ($I$) for disc | $I = \dfrac{1}{2} m r^2 = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 2 \times (0.5)^2 = 0.25\ \mathrm{kg\,m}^2$ |

| Angular acceleration ($\alpha$) | $\alpha = \dfrac{\tau}{I} = \dfrac{1}{0.25} = 4\, \mathrm{rad/s^2}$ |

Applications and Significance in Examination

Dynamics of rotational motion about a fixed axis is frequently tested in competitive exams due to its links with several topics in mechanics, electromagnetism, and modern physics. Mastery of these principles aids in understanding real-world mechanical systems and physical devices.

For further study and complete resources, visit Dynamics Of Rotational Motion About A Fixed Axis.

FAQs on Understanding Rotational Motion About a Fixed Axis

1. What is rotational motion about a fixed axis?

Rotational motion about a fixed axis is a type of motion where a rigid body turns around a specific, unmoving line called its axis of rotation. In this motion, all points of the object move in circles centered on the axis.

- Axis of rotation remains stationary

- Each point moves in a circular path perpendicular to the axis

- Common in systems like wheels, doors, fans

2. What are the key differences between translational and rotational motion?

Translational motion involves movement in a straight line, while rotational motion is about spinning around a fixed axis. Key differences include:

- In translational motion, every point on the body moves the same distance in the same direction

- In rotational motion, different points move in separate circles and cover different distances

- Rotational motion uses angular displacement, velocity, acceleration, whereas translational uses linear versions of these terms

5. State and explain the rotational analog of Newton’s Second Law.

The rotational form of Newton’s Second Law states that the angular acceleration of a body is directly proportional to the net torque acting on it and inversely proportional to its moment of inertia.

- Expressed as: \( \tau = I\alpha \)

- Where \tau is torque, I is moment of inertia, and \alpha is angular acceleration

- Essential for quantitative problems in CBSE exams

7. What factors affect the moment of inertia of a body?

The moment of inertia is influenced by how the mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation. Main factors include:

- Total mass of the body

- Distribution of mass (closer or farther from the axis)

- Shape and size of the object

- Position and orientation of the axis of rotation

8. Explain the principle of conservation of angular momentum with examples.

The conservation of angular momentum states that if no external torque acts on a system, its total angular momentum remains constant. Examples:

- A spinning skater pulling arms in to spin faster (reduces moment of inertia, increases angular velocity)

- Planetary motion around the sun

11. Why is torque called the moment of force?

Torque is often called the moment of force because it measures the rotational effect produced by a force acting at a distance from a pivot point.

- Similar to ‘moment’ in linear systems

- Describes tendency of force to cause rotation

12. What is the SI unit of moment of inertia?

The SI unit of moment of inertia is kilogram metre squared (kg·m2). This is because it involves both mass and the square of distance from the axis. This is a direct exam-oriented fact for CBSE students.