How Does Hydrostatics Work? Principles, Formulas, and Real-World Uses

Hydrostatics is a fundamental branch of fluid mechanics that studies fluids at rest and the effects of forces exerted by static fluids on submerged or floating bodies. It explains the properties of hydrostatic pressure, principles such as Pascal's law, and analyzes how fluids transmit force across surfaces at equilibrium.

Definition and Scope of Hydrostatics

Hydrostatics, a domain within fluid mechanics, focuses on the conditions and properties of fluids that are stationary. It examines the pressure distribution in fluids at rest and evaluates the resulting forces on objects immersed or partially immersed in such fluids. Hydrostatics refers to systems that have no fluid flow or relative motion between fluid layers.

Applications of hydrostatics are observed in engineering, geophysics, and everyday phenomena, including measuring fluid pressure, designing hydraulic lifts, and determining buoyant forces. For a comprehensive overview, refer to Hydrostatics Overview.

Hydrostatic Pressure and Its Characteristics

Hydrostatic pressure is the pressure exerted by a stationary fluid at a certain depth due to the weight of the fluid above. It is directly proportional to both the density of the fluid and the vertical depth measured from the free surface.

The hydrostatics formula for pressure at any depth $h$ is given by:

$P = \rho \, g \, h$

Here, $P$ represents hydrostatic pressure, $\rho$ is fluid density, $g$ denotes acceleration due to gravity, and $h$ is the depth below the fluid surface. The pressure at a point within a static fluid acts equally in all directions and is perpendicular to any surface in contact with the fluid.

Further analysis of fluid pressure concepts can be found at Understanding Pressure.

Pascal’s Law in Hydrostatics

Pascal's law is a foundational principle in hydrostatics. It states that when an external pressure is applied to a confined, incompressible fluid, the pressure is transmitted undiminished in all directions within the fluid. This allows hydraulic systems to multiply forces efficiently.

The mathematical statement of Pascal’s law can be written as:

$\Delta P = \dfrac{F}{A}$

where $\Delta P$ is the pressure applied, $F$ is the force, and $A$ is the area over which the force is distributed. Pascal’s law underpins the operation of hydraulic presses, brakes, and other devices. For more detail, visit Pascal's Law of Hydrostatics.

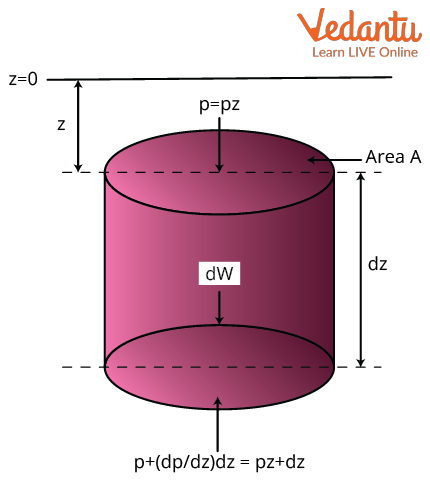

Hydrostatics Equations and Pressure Derivation

The variation of hydrostatic pressure with depth is derived using a fluid element of infinitesimal thickness $dz$ at a depth $z$. Considering equilibrium and uniform density $\rho$, the change in pressure $dp$ over $dz$ is:

$\dfrac{dp}{dz} = -\rho g$

Integrating over the depth from the free surface to depth $h$:

$P = \rho g h$

This mathematical relationship is central to all hydrostatics problems and is widely used in both theoretical and practical applications.

Centre of Pressure and Forces on Submerged Surfaces

The centre of pressure is the point where the total hydrostatic force acts on a submerged or partially submerged surface. It is not necessarily at the centroid unless the surface is horizontal or the pressure distribution is uniform.

For a vertical submerged plane of area $A$ at a depth $h$, the total hydrostatic force is $F = \rho g h_\text{c} A$, where $h_\text{c}$ is the depth to the centroid. The position of the centre of pressure is given by $h_\text{cp} = \dfrac{I_G + A h_c^2}{A h_c}$, where $I_G$ is the second moment of area about the horizontal axis through the centroid.

This analysis is essential for designing structures like dams and gates where precise location and magnitude of hydrostatic forces must be evaluated.

Buoyant Force and Law of Floatation

Any object immersed in a fluid experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. This is known as the buoyant force, established by Archimedes' principle, which is a direct consequence of hydrostatics. The law of floatation states that a body floats when its weight equals the buoyant force.

For more discussion on upthrust and floatation, refer to Upthrust and Floatation Law.

Hydrostatics in Curved Surfaces

When analyzing hydrostatic forces on curved surfaces, the force components must be resolved horizontally and vertically. The vertical component equals the weight of fluid directly above the curved surface, while the horizontal component equals the force on the vertical projection of the surface.

Such analyses are important for fluid storage tanks, hydraulic structures, and underwater vessels.

Real-World Applications of Hydrostatics

Hydrostatics is applied in barometers for measuring atmospheric pressure, hydraulic presses for mechanical advantage, and braking systems in vehicles. The Mercury barometer utilizes a column of mercury to directly indicate atmospheric pressure based on hydrostatic principles. Explore hydraulic press operations at Hydraulic Press Principles.

Hydrostatics also plays a key role in the design of swimming pools, dams, submarines, and laboratory equipment.

Comparison Table: Key Hydrostatics Quantities

| Quantity | Expression/Definition |

|---|---|

| Hydrostatic Pressure ($P$) | $P = \rho g h$ |

| Buoyant Force ($F_B$) | $F_B = \rho_\text{fluid} g V_\text{disp}$ |

| Pascal's Law | $\Delta P = \dfrac{F}{A}$ |

| Centre of Pressure ($h_{cp}$) | $\dfrac{I_G + A h_c^2}{A h_c}$ |

Common Hydrostatics Examples

- Pressure at the base of a water tank

- Buoyant force on a submerged object

- Force on a dam wall due to water

- Lift produced by a hydraulic jack

- Operation of a Mercury barometer

The quantitative analysis for these examples relies on the hydrostatics equations and physical laws discussed above.

Related Concepts in Fluid Mechanics

Hydrostatics is distinct from fluid dynamics, which studies fluids in motion. Other related areas include Bernoulli’s principle for moving fluids and viscosity for internal fluid friction. For comparison, visit Bernoulli's Principle Explained.

Summary of Key Points in Hydrostatics

- Hydrostatics analyzes fluids at rest and resulting pressures

- Pressure increases linearly with depth in an incompressible fluid

- Pascal’s law explains force transmission in fluids

- Buoyant force equals weight of displaced fluid

- Centre of pressure is critical in hydrostatics problems

FAQs on Understanding Hydrostatics: Key Concepts and Applications

1. What is hydrostatics and why is it important?

Hydrostatics is the branch of physics that studies fluids at rest and the forces exerted by or upon these fluids.

Key points:

- Hydrostatics helps us understand how fluids behave in containers and natural environments.

- It is fundamental for engineering, fluid mechanics, and atmospheric studies.

- Examples include designing dams, submarines, and hydraulic systems.

2. What are the basic laws of hydrostatics?

Hydrostatics is governed by several essential laws that explain the behavior of fluids at rest.

Key laws include:

- Pascals's Law: Pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted undiminished throughout the fluid.

- Archimedes' Principle: A body immersed in a fluid experiences an upthrust equal to the weight of fluid displaced.

- Law of Fluid Pressure: Pressure increases with depth in a stationary fluid.

3. What is Pascal’s Law with example?

Pascal's Law states that pressure applied to an enclosed fluid is transmitted equally in all directions.

Example:

- In a hydraulic lift, applying force to a small piston increases the pressure, which is transmitted to a larger piston to lift heavy loads.

4. State Archimedes’ Principle and its applications.

Archimedes’ Principle explains how objects float or sink in fluids due to upthrust.

Summary:

- An object immersed in a fluid experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by it.

- Applications: Designing ships and boats, measuring body volume, and checking the purity of gold.

5. How does pressure vary with depth in a fluid?

In a stationary liquid, pressure increases linearly with depth.

Explanation:

- Deeper points experience greater pressure due to the weight of liquid above.

- Calculation: P = hρg, where h = depth, ρ = fluid density, g = acceleration due to gravity.

6. What are common examples of hydrostatic pressure in daily life?

Hydrostatic pressure affects many everyday phenomena.

Examples:

- Water pressure in household plumbing.

- Pressure at the base of a dam.

- Blood pressure in veins and arteries.

- Atmospheric pressure felt at sea level or high altitudes.

7. How is the buoyant force calculated?

Buoyant force is determined by Archimedes’ Principle and relies on the displaced fluid’s weight.

Calculation:

- Buoyant Force = Weight of fluid displaced

- Formula: F = ρ × V × g

- Where ρ = density of fluid, V = volume displaced, g = acceleration due to gravity.

8. What factors determine whether an object will float or sink in a fluid?

An object floats or sinks based on the relationship between its density and the fluid's density.

Key factors:

- If object's density < fluid density: it floats.

- If object's density > fluid density: it sinks.

9. What is meant by atmospheric pressure and how is it measured?

Atmospheric pressure is the force per unit area exerted by the Earth's atmosphere on surfaces.

Measurement:

- Measured using a barometer.

- Standard atmospheric pressure at sea level is 1 atm = 101,325 Pa (pascals).

10. Why do dams have a broader base?

Dams have a broader base to withstand the increasing hydrostatic pressure at greater depths.

Main reasons:

- Pressure increases with depth, so more strength is required at the bottom.

- A wide base distributes the pressure and prevents the dam from collapsing.

11. Define density and relative density.

Density is the mass per unit volume of a substance, while relative density compares a substance’s density to that of water.

Formulas:

- Density (ρ) = Mass/Volume (kg/m3)

- Relative Density = Density of substance/Density of water