How Do Nucleophiles Work in Chemical Reactions?

Nucleophile may be a word used to refer to substances that tend to give electron pairs to electrophiles so as to make chemical bonds with them. Any ion or molecule having an electron pair that is free or a pi bond containing 2 electrons has the ability to behave like nucleophiles.

In other words, nucleophiles are unit Lewis bases. The word “nucleophiles” suggests that (“nucleus loving”, or “positive-charge loving”). Read ahead to know more about ambient nucleophiles, their types and examples.

What is a Nucleophile?

Nucleophiles are essentially electron-rich species that have the capacity to donate electron pairs, as mentioned earlier. Due to this electron pair donating tendency, all nucleophiles are Lewis Bases.

Reaction of Nucleophile

Nucleophilic Name Meaning

The phrase ‘nucleophile’ may be cut up into parts, particularly nucleus and philos. Philos is the Greek phrase for ‘love’. Therefore, nucleophiles may be thought of as Nucleus Loving species.

Terminologies of Nucleophile

The nucleophilic nature of a species describes the affinity of the species to the positively charged nucleus. Nucleophilicity is a phrase used to evaluate the nucleophilic individual of various nucleophiles in a query. It also can be referred to as the nucleophilic strength of a species.

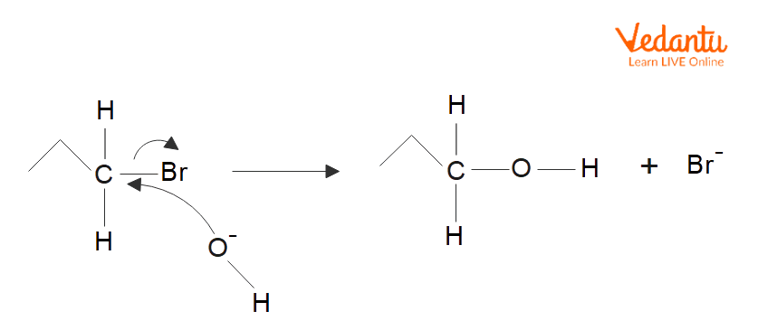

Nucleophilic substitution is a form of reaction that takes place while an electron-rich nucleophile selectively donates a charged (or a partially charged) atom in a molecule and replaces a leaving group with the help of bonding with the positively charged species.

Solvolysis is a form of nucleophilic substitution reaction in which the nucleophile in question is a solvent molecule. A correct instance of this sort of nucleophilic solvent is water, and the solvolysis with water is also known as hydrolysis.

Types of Nucleophiles

Halogens: The diatomic shape of a halogen does not show the nucleophilic reaction. However, the anionic forms of those halogens are good nucleophiles. An example of this is: diatomic iodine (I2) , which does not act as a nucleophile, while I– is the most powerful nucleophile in a polar, protic solvent.

Carbon: Carbon acts as a nucleophile in lots of organometallic reagents and additionally in enols. Some examples of compounds in which carbon acts as a nucleophile consist of Grignard Reagents, Organolithium Reagents, and n-butyllithium.

Oxygen: The hydroxide ion is a remarkable example of a nucleophile in which the electron pair is donated with the help of using the oxygen atom. Other examples consist of alcohol and hydrogen peroxide. It is vital to know that no nucleophilic attacks arise in the intermolecular hydrogen bonding that takes place in lots of compounds containing oxygen and hydrogen.

Sulphur: Due to the huge size, the relative ease in its polarisation, and the easily available lone pairs, sulphur has many nucleophilic qualities. Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) is an example of a nucleophile containing sulphur.

Nitrogen: Nitrogen is used in forming many nucleophiles along with amines, azides, ammonia, and nitrides. Even amides are recognised to show nucleophilic qualities.

Ambident Nucleophiles

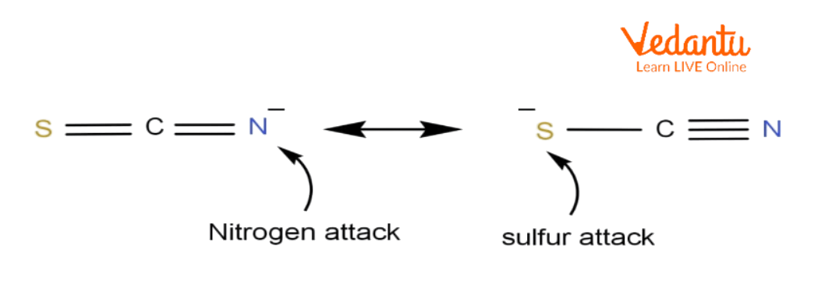

What are ambient nucleophiles? An ambident nucleophile is an anionic nucleophile whose negative charge is delocalised by resonance over 2 unlike atoms or over 2 like but non-equivalent atoms. The most common ambident nucleophiles are enolate ions.

Attacks from those varieties of nucleophiles can regularly bring about the formation of multiple products. An ambident nucleophile example is the thiocyanate ion which has the chemical formulation of SCN–. This ion can execute nucleophilic substitution from both the sulphur atom or the nitrogen atom.

The nucleophilic substitution reactions of alkyl halides concerning this ion regularly bring about the formation of an aggregate of the subsequent products: alkyl isothiocyanates with the chemical formulation R-NCS and alkyl thiocyanates with the chemical formulation R-SCN. Therefore, an ambident nucleophile may be considered as an anionic nucleophile where the negative charge of the ion is delocalised over distinct atoms with the help of resonance effects.

Ambident Nucleophile Examples

Ambident nucleophiles are anionic which have nucleophilic sites (poor sites) through which they could attack. As a result, a new product is formed. Some of the ambient nucleophile examples are cyanide and thiocyanate.

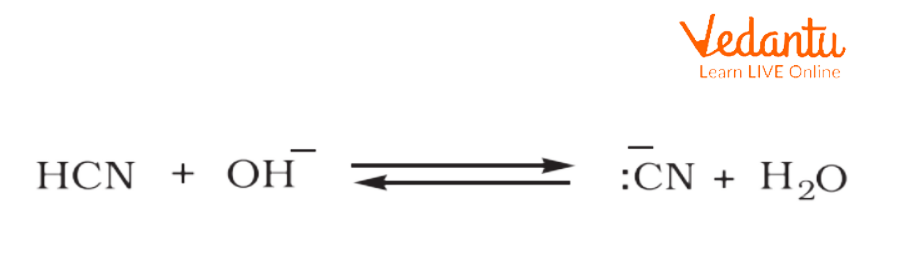

Cyanide

Thiocyanate

Important Question

Q. Which of the following is an ambient nucleophile?

H+

CN-

OH-

Cl+

Ans. The correct answer is (b) CN- .

Explanation: Either the carbon or N atom in CN- can act as electron donor to the haloalkane. Nucleophiles that have more than one site through which the reaction will occur are referred to as ambident nucleophiles.

Conclusion

A nucleophile that can execute nucleophilic attacks from two or more different places in the molecule (or ion) is called an ambident nucleophile. Attacks from these types of nucleophiles can often result in the formation of more than one product. Nucleophiles consist of electrons and instead are attracted towards the nucleus. They are either negatively or neutrally charged and are donors of electrons. Electrons move from low-density areas to high-density areas.

FAQs on Nucleophile: Meaning, Types & Key Reactions

1. What is a nucleophile in organic chemistry? Provide some common examples.

A nucleophile, which means "nucleus-loving," is a chemical species that donates an electron pair to an electron-deficient centre (an electrophile) to form a new covalent bond. Nucleophiles are electron-rich. They are typically either negatively charged ions (anions) or neutral molecules with at least one lone pair of electrons. Common examples include the hydroxide ion (OH⁻), chloride ion (Cl⁻), water (H₂O), and ammonia (NH₃).

2. What are the primary types of nucleophiles?

Nucleophiles are generally classified based on their charge or the donating atom. The main types include:

- Anionic Nucleophiles: These are negatively charged species and are often strong nucleophiles. Examples include halide ions (F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), the hydroxide ion (OH⁻), and the cyanide ion (CN⁻).

- Neutral Nucleophiles: These are neutral molecules that contain an atom with a lone pair of electrons. Examples include water (H₂O), ammonia (NH₃), and alcohols (R-OH).

- Ambident Nucleophiles: These are species that have two or more different atoms that can act as the nucleophilic centre. For example, the nitrite ion (NO₂⁻) can attack with either the nitrogen or the oxygen atom.

3. What are the major types of reactions where nucleophiles are involved?

Nucleophiles are central to two fundamental types of organic reactions:

- Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions (SN): In these reactions, a nucleophile attacks a substrate and replaces another group, known as the 'leaving group'. The hydrolysis of an alkyl halide by an aqueous alkali is a classic example. These are further classified as SN1 and SN2 reactions based on their mechanism.

- Nucleophilic Addition Reactions: Here, a nucleophile adds to an electron-deficient double or triple bond, most commonly the carbon-oxygen double bond of a carbonyl group (aldehydes and ketones). This breaks the pi (π) bond and forms a new single bond.

4. How does a nucleophile fundamentally differ from an electrophile?

The fundamental difference between a nucleophile and an electrophile lies in their roles during bond formation. A nucleophile is an electron-rich species that donates an electron pair. In contrast, an electrophile ('electron-loving') is an electron-deficient species that accepts an electron pair. In any reaction between the two, the nucleophile attacks the electrophile. For example, in the reaction between ammonia (NH₃, the nucleophile) and a carbocation (CH₃⁺, the electrophile), ammonia donates its lone pair of electrons.

5. Why is a nucleophile considered a type of Lewis base?

A nucleophile is considered a Lewis base because its chemical behaviour fits the definition of a Lewis base perfectly. According to the Lewis theory, a Lewis base is any species that can donate a pair of electrons to form a covalent bond. Since a nucleophile's primary function is to donate an electron pair to an electrophile (a Lewis acid), every nucleophile is, by definition, a Lewis base.

6. How is it determined whether a species will act as a nucleophile or a base in a reaction?

Many species can act as both a nucleophile and a base. The outcome depends on several factors, primarily the structure of the substrate and the attacking species.

- Steric Hindrance of the Substrate: If the electrophilic carbon is crowded (e.g., in a tertiary alkyl halide), the species is more likely to act as a base and abstract a proton, leading to an elimination reaction. If the carbon is accessible (primary), it favours acting as a nucleophile, leading to substitution.

- Steric Hindrance of the Attacking Species: A bulky species, like tert-butoxide, is a strong base but a poor nucleophile because it is too large to easily attack a carbon atom. It prefers to remove a small, exposed proton.

7. What is the key difference between the concepts of nucleophilicity and basicity?

Although related, nucleophilicity and basicity are distinct concepts. Basicity is a thermodynamic property that measures a substance's ability to accept a proton (H⁺), described by an equilibrium constant (Kₐ or Kₑ). In contrast, nucleophilicity is a kinetic property that measures the rate at which a nucleophile attacks an electron-deficient atom. A strong base is not always a strong nucleophile. For instance, the iodide ion (I⁻) is a very strong nucleophile but a weak base, whereas the fluoride ion (F⁻) is a stronger base but a weaker nucleophile in polar protic solvents.