How Do Isotherms Work in Real-World Chemistry?

The basis of isotherms is a process called adsorption. When the molecular species accumulate at the surface of a material rather than in its bulk, the process is known as adsorption. It is essentially a surface phenomenon where the accumulating species is called adsorbate and the material on which adsorption takes place is called adsorbent. The adsorbate is usually a gas and the adsorbent, a solid surface.

Factors Affecting Rate of Adsorption

Adsorption is of two types- physical (physisorption) and chemical (chemisorption). Physisorption occurs on account of formation of weak Vander Waal forces. However, if chemical bond formation takes place it is termed as chemisorption. There are multiple factors that affect the rate of adsorption. Some increase the rate while others may retard it. A factor may affect different types of adsorptions differently. Effect of a factor can be studied by changing one factor and keeping others constant.

Nature of Gas

Higher is the liquefaction tendency of gas, higher is its adsorption tendency. Liquefaction tendency of a gas can be assumed by considering attractive forces. Higher the attractive forces between gas particles, more is their liquefaction tendency and therefore, more is their adsorption.

Nature of Solid

This factor completely depends on the surface area of the solid. More be the surface area of solid, more be the extent of adsorption.

For physisorption, the order of adsorption according to surface area is Solid piece < Powdered solid < Sol of solid

For chemisorption, d and f block elements have more adsorption tendency due to vacant valencies.

Temperature

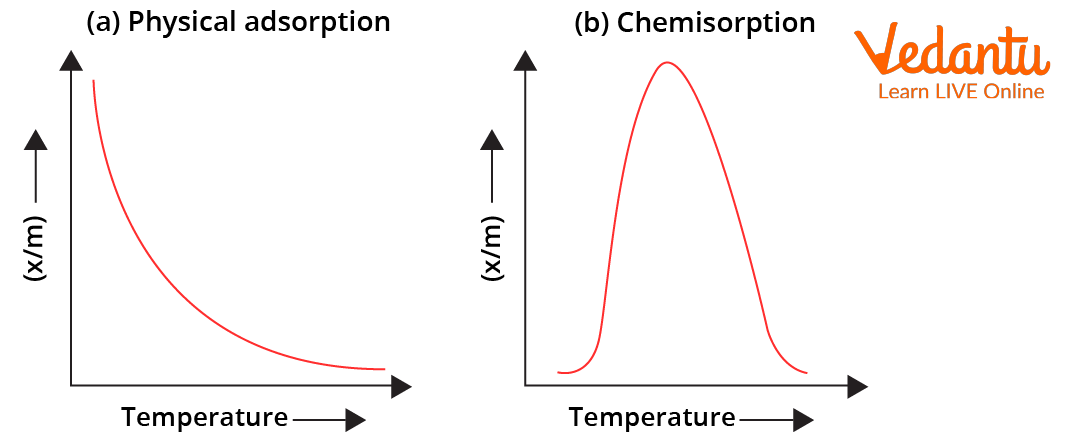

For physisorption, adsorption tendency decreases with increase in temperature due to decrease in attractive forces for chemisorption, adsorption tendency initially increases up to a certain extent (due to increase in fraction of molecules possessing activation energy) and then decreases.

Variation of Extent of Adsorption $(\frac{x}{m})$ with Temperature

Pressure

Adsorption of gases results in decrease in volume of the system. Therefore, it is expected that at a given temperature, the extent of adsorption will increase with increase in pressure of gas. The curves which enable us to understand and derive a mathematical relation between extent of adsorption and pressure, at a constant temperature, are called isotherms.

Variation of Extent of Adsorption $(\frac{x}{m})$ with Pressure (isotherm)

Isotherms

Since adsorption depends on various factors like temperature, pressure, surface area, etc., it is difficult to understand the dependency relation of adsorption tendency and all factors together. Therefore, all factors are kept constant while one is changed to study the effect on adsorption. When temperature is kept constant while altering the pressure, a graph called isotherm is plotted.

As seen from the isotherm the relation between pressure and adsorption is as follows:

At low pressure: Adsorption is directly proportional to pressure

At high pressure: Adsorption is independent to pressure (reaches saturation)

In between the above pressure conditions: Adsorption varies with $P^{x}$ where, $x<1$

To derive a mathematical relation from the above graph, attempts were made by two different scientists- Herbert Freundlich and Irving Langmuir.

Freundlich Isotherm

In 1909, Freundlich gave an empirical relationship between the quantity of gas adsorbed by unit mass of solid adsorbent and pressure at a particular temperature. The relationship can be expressed by the following equation:

$\frac{x}{m} \ = \ k.P^{\frac{1}{n}}$

Where, $\frac{x}{m} \ = $ extent of adsorption (x is mass of adsorbate and m is mass of adsorbent when dynamic equilibrium is achieved)

K and n = constants that depend on adsorbent and adsorbate at particular temperatures (value of $\frac{1}{n}$ lies between $0.1 \ to \ 0.5$)

$P \ = $ pressure

Plotting the Isotherm

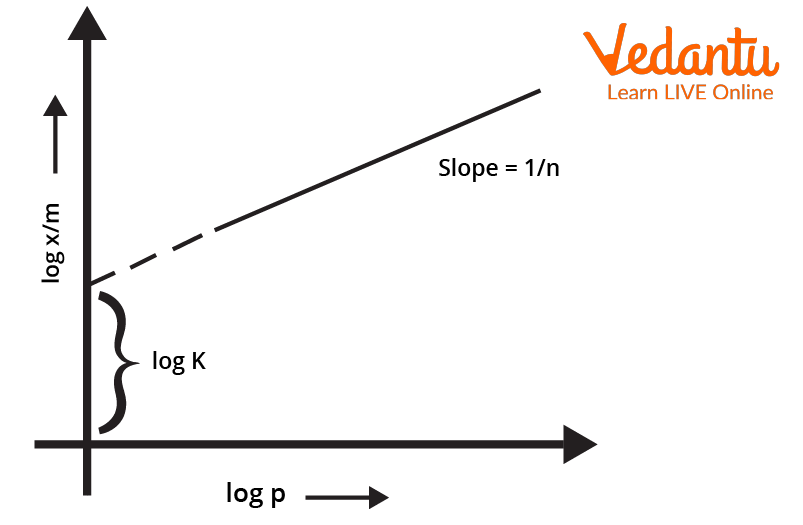

To plot the freundlich isotherm, the log of the equation $\frac{x}{m} \ = \ k.P^{\frac{1}{n}}$ is considered. The equation thus becomes $log \frac{x}{m} \ = \ logk \ + \ \frac{1}{n}logP$

The validity of Freundlich isotherm can be verified by plotting the graph according to the above equation. If it turns out to be a straight line, the isotherm is valid otherwise not.

Log Graph of Freundlich Isotherm

Credibility of the Freundlich Isotherm

Freundlich isotherm explains the behaviour of adsorption in an approximate manner in an approximate manner. The value of $\frac{1}{n}$ lies between 0 and 1 (probable range $0.1 \ to \ 0.5$). Thus, the Freundlich isotherm equation holds well over a limited range of pressure

When $\frac{1}{n} \ = \ 0, \ \frac{x}{m} \ =$ constant, the adsorption is independent of pressure (Case at very high pressures)

When $\frac{1}{n} \ = \ 1, \ \frac{x}{m} \ = \ k.P, $ the adsorption varies directly with pressure (Case at very low pressures)

Experimentally, both the conditions are observed. Therefore, although Freundlich isotherm can explain the adsorption tendency with variation in pressure at certain points, it does not justify the entire graph.

Since gases approach saturation at very high pressure, Freundlich isotherms fails at high pressure as $\frac{x}{m} \ = \ k.P^{\frac{1}{n}}$ is not justified at high pressure.

Langmuir Isotherm

It is a more widely accepted isotherm. It assumes that the adsorbed gas is ideal and only a monolayer is formed by it. Therefore, it is more accurately valid for chemisorption. Here, all adsorption sites are considered equivalent and the rate of adsorption is proportional to vacant sites. It is also assumed that adsorption is reversible and at equilibrium, rate of adsorption and desorption are equal.

Langmuir Equation and Credibility

According to Langmuir, the equation for plotting an adsorption isotherm is $\frac{x}{m} \ = \frac{a.P}{1 \ + \ bP}$

Where, $\frac{x}{m} \ = $ extent of adsorption (x is mass of adsorbate and m is mass of adsorbent when dynamic equilibrium is achieved)

a and b = Langmuir constants

P = pressure

At very high pressure, $1 \ + \ bP \approx \ b.P$ , therefore, according to above equation- $\frac{x}{m} \ = \frac{a.P}{b.P} \ = \ \frac{a}{b}$

At very low pressure, $1 \ + \ bP \approx \ 1$ , therefore, according to above equation- $\frac{x}{m} \ = \ a.P$

Therefore, Langmuir isotherm is valid for high as well as low pressures.

Conclusion

Adsorption, the process of accumulation of an adsorbate (gas) on an adsorbent (solid surface) is of two types- chemisorption and physisorption. Multiple factors like surface area, temperature, pressure, etc. affect adsorption. At constant temperature, a graph depicting the variation of adsorption with change in pressure is called an isotherm. Two attempts were made to derive equations for adsorption. The Freundlich isotherm equation is represented by $\frac{x}{m} \ = \ k.P^{\frac{1}{n}}$ . Only if the log of this equation is a straight line, the freundlich isotherm is valid. It fails at high pressure. The Langmuir isotherm equation is depicted by $\frac{x}{m} \ = \frac{a.P}{1 \ + \ bP}$ . It is more credible since it is valid at high as well as low pressure conditions.

FAQs on Isotherm: Definition, Examples & Applications

1. What is an adsorption isotherm in the context of chemistry?

An adsorption isotherm is a graph that illustrates the relationship between the amount of a substance (adsorbate) that accumulates on the surface of another material (adsorbent) and the pressure or concentration of the adsorbate at a constant temperature. The term 'iso' means same, and 'therm' refers to temperature. It essentially shows how much gas or solute is adsorbed as pressure or concentration changes, keeping the temperature fixed.

2. What are the two main types of adsorption isotherms studied in chemistry?

The two primary models for adsorption isotherms that are widely studied are:

- Freundlich Adsorption Isotherm: An empirical model that describes multilayer, non-ideal, and reversible adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. It works well at low to moderate pressures.

- Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm: A theoretical model based on specific assumptions, such as the formation of a single layer (monolayer) of adsorbate on a homogeneous surface where all adsorption sites are equivalent. It is generally more accurate for chemisorption.

3. How is a chemical isotherm different from an isobar or an isochore?

These terms describe different thermodynamic processes based on which property remains constant:

- An isotherm describes a process or relationship where the temperature remains constant.

- An isobar describes a process where the pressure remains constant.

- An isochore describes a process where the volume remains constant.

4. What is the formula for the Freundlich adsorption isotherm and what do its variables represent?

The Freundlich adsorption isotherm is given by the empirical formula:

x/m = k * P^(1/n)

Where:

- x/m is the extent of adsorption, representing the mass of the adsorbate (x) per unit mass of the adsorbent (m).

- P is the equilibrium pressure of the adsorbate gas.

- k and n are constants that depend on the nature of the adsorbate and adsorbent at a particular temperature. The value of 'n' is always greater than one.

5. Why does the Freundlich isotherm model fail at high pressures?

The Freundlich isotherm fails at high pressures because it is an empirical model that doesn't account for the saturation of the adsorbent's surface. At very high pressures, the surface becomes fully covered with a layer of adsorbate molecules. Once this saturation point is reached, the extent of adsorption (x/m) becomes constant and no longer increases with pressure. The Freundlich equation, however, predicts that adsorption will keep increasing indefinitely, which is physically impossible.

6. What are the key assumptions that form the basis of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm?

The Langmuir model is based on several key theoretical assumptions:

- The surface of the adsorbent is uniform, meaning all adsorption sites are energetically equivalent.

- Adsorption is restricted to a monolayer; once a site is occupied, no further adsorption can occur there.

- The adsorbed molecules do not interact with each other on the surface.

- The process involves a dynamic equilibrium, where the rate of adsorption (molecules sticking to the surface) is equal to the rate of desorption (molecules leaving the surface).

7. How does a change in temperature generally affect an adsorption isotherm?

Adsorption is typically an exothermic process (releases heat, ΔH is negative). According to Le Chatelier's principle, if you increase the temperature of an exothermic system at equilibrium, the equilibrium will shift to favour the endothermic (reverse) reaction. Therefore, for the same pressure, the amount of gas adsorbed will decrease as the temperature increases. This is why a separate isotherm curve is needed for each different temperature.

8. What are some important real-world applications of adsorption isotherms?

Understanding adsorption isotherms is crucial for many practical applications, including:

- Gas Masks: Designing activated charcoal filters that effectively adsorb toxic gases from the air.

- Industrial Catalysis: Determining the efficiency of solid catalysts (like in the Haber-Bosch process for ammonia) by studying how reactants adsorb onto their surfaces.

- Water Purification: Using materials like activated carbon or zeolites to remove impurities and pollutants from water.

- Chromatography: Separating chemical mixtures based on the differential adsorption of components onto a stationary phase.