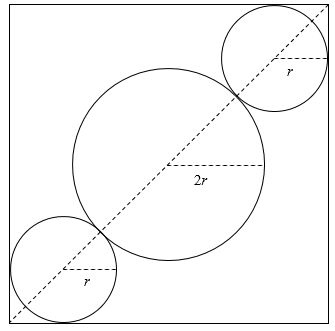

Three circles of radii \[r\], \[2r\], and \[r\] are drawn with their centres on the diagonal of a square, touching one another and the square as shown. What is the ratio of the

radius of the smaller circles to the side of the square?

Answer

563.7k+ views

Hint: Here, we need to find the ratio of the radius of the smaller circle and the side of the square. We will first construct the perpendiculars and use the properties of a square to find the measure of the angles. We will then use the trigonometric ratio of tangent to find the length of the diagonal in terms of the radius of the smaller circle. Then, we will use Pythagoras’s theorem to find the required ratio of the radius of the smaller circle and the side of the square.

Complete step-by-step answer:

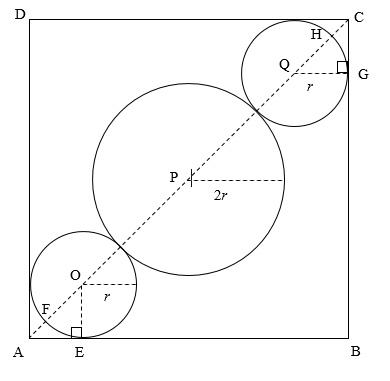

First, we will mark the points and construct perpendiculars in the diagram.

Here, ABCD is the square, and OE is perpendicular to AB, and QG is perpendicular to BC.

OE, OF, QG, and QH are the radii of the smaller circles.

Thus, we get

\[OE = OF = QG = QH = r\]

AC is the diagonal of square ABCD.

We know that each interior angle of a square is a right angle.

Therefore, we get

\[\angle DAB = \angle BCD = 90^\circ \]

The diagonal of a square bisect the interior angles.

Therefore, we get

\[\angle CAB = \dfrac{1}{2}\angle DAB = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 90^\circ = 45^\circ \]

\[\angle ACB = \dfrac{1}{2}\angle BCD = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 90^\circ = 45^\circ \]

Thus, we get

\[\angle OAE = \angle CAB = 45^\circ \]

\[\angle QCG = \angle ACB = 45^\circ \]

We can observe that the triangle OAE is a right angled triangle.

The tangent of an angle \[\theta \] in a right angled triangle is given by \[\tan \theta = \dfrac{{{\rm{Perpendicular}}}}{{{\rm{Base}}}}\].

Therefore, in triangle OAE, we get

\[\tan 45^\circ = \dfrac{{OE}}{{AE}}\]

Substituting \[\tan 45^\circ = 1\] in the equation, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow 1 = \dfrac{{OE}}{{AE}}\\ \Rightarrow OE = AE\end{array}\]

Thus, we get

\[ \Rightarrow OE = AE = r\]

We will use the Pythagoras’s theorem in the right angled triangle OAE.

In triangle OAE, OA is the hypotenuse, AE is the base, and OE is the height.

Therefore, in triangle OAE, we get

\[O{A^2} = A{E^2} + O{E^2}\]

The side OA is the sum of the lengths AF and FO.

Substituting \[OA = AF + OF\] and \[OE = AE = r\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {AF + OF} \right)^2} = {r^2} + {r^2}\]

Substituting \[OF = r\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {AF + r} \right)^2} = 2{r^2}\]

Taking the square root of both sides, we get

\[ \Rightarrow AF + r = \sqrt 2 r\]

Thus, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AF = \sqrt 2 r - r\\ \Rightarrow AF = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\end{array}\]

Similarly, using the triangle QCG, we get \[CH = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\].

The diagonal AC is the sum of the lengths AF, CH, and the diameters of the three circles.

Therefore, we get

\[ \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right) + 2r + 2\left( {2r} \right) + 2r + r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\]

Simplifying the expression, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right) + 2r + 4r + 2r + r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\\ \Rightarrow AC = \sqrt 2 r - r + 2r + 4r + 2r + \sqrt 2 r - r\end{array}\]

Adding and subtracting the like terms, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AC = 2\sqrt 2 r + 6r\\ \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\end{array}\]

Now, we can observe that triangle ABC is a right angled triangle because the interior angles of a square are right angles.

Let the sides AB, BC, CD, and AD of the square be of length \[x\].

Thus, using the Pythagoras’s theorem in triangle ABC, we get

\[A{C^2} = A{B^2} + B{C^2}\]

Substituting \[AB = BC = x\] and \[AC = r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)} \right)^2} = {x^2} + {x^2}\]

Simplifying the expression, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {r^2}{\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)^2} = 2{x^2}\]

Taking the square root of both sides, we get

\[ \Rightarrow r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right) = \sqrt 2 x\]

Dividing both sides of the equation by \[x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\], we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow \dfrac{{r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}}{{x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}} = \dfrac{{\sqrt 2 x}}{{x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}}\\ \Rightarrow \dfrac{r}{x} = \dfrac{{\sqrt 2 }}{{2\sqrt 2 + 6}}\end{array}\]

We get the ratio of the radius of the smaller circles and the side of the square as \[\dfrac{{\sqrt 2 }}{{2\sqrt 2 + 6}}\].

Note: We used the Pythagoras’s theorem in the solution. The Pythagoras’s theorem states that the square of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is equal to the sum of squares of the other two sides, that is \[{\rm{Hypotenus}}{{\rm{e}}^2} = {\rm{Bas}}{{\rm{e}}^2} + {\rm{Perpendicula}}{{\rm{r}}^2}\]. The hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is its longest side. Pythagora's theorem can be used only in right angled triangles. For other types of triangles, we use Heron’s formula.

Complete step-by-step answer:

First, we will mark the points and construct perpendiculars in the diagram.

Here, ABCD is the square, and OE is perpendicular to AB, and QG is perpendicular to BC.

OE, OF, QG, and QH are the radii of the smaller circles.

Thus, we get

\[OE = OF = QG = QH = r\]

AC is the diagonal of square ABCD.

We know that each interior angle of a square is a right angle.

Therefore, we get

\[\angle DAB = \angle BCD = 90^\circ \]

The diagonal of a square bisect the interior angles.

Therefore, we get

\[\angle CAB = \dfrac{1}{2}\angle DAB = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 90^\circ = 45^\circ \]

\[\angle ACB = \dfrac{1}{2}\angle BCD = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 90^\circ = 45^\circ \]

Thus, we get

\[\angle OAE = \angle CAB = 45^\circ \]

\[\angle QCG = \angle ACB = 45^\circ \]

We can observe that the triangle OAE is a right angled triangle.

The tangent of an angle \[\theta \] in a right angled triangle is given by \[\tan \theta = \dfrac{{{\rm{Perpendicular}}}}{{{\rm{Base}}}}\].

Therefore, in triangle OAE, we get

\[\tan 45^\circ = \dfrac{{OE}}{{AE}}\]

Substituting \[\tan 45^\circ = 1\] in the equation, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow 1 = \dfrac{{OE}}{{AE}}\\ \Rightarrow OE = AE\end{array}\]

Thus, we get

\[ \Rightarrow OE = AE = r\]

We will use the Pythagoras’s theorem in the right angled triangle OAE.

In triangle OAE, OA is the hypotenuse, AE is the base, and OE is the height.

Therefore, in triangle OAE, we get

\[O{A^2} = A{E^2} + O{E^2}\]

The side OA is the sum of the lengths AF and FO.

Substituting \[OA = AF + OF\] and \[OE = AE = r\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {AF + OF} \right)^2} = {r^2} + {r^2}\]

Substituting \[OF = r\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {AF + r} \right)^2} = 2{r^2}\]

Taking the square root of both sides, we get

\[ \Rightarrow AF + r = \sqrt 2 r\]

Thus, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AF = \sqrt 2 r - r\\ \Rightarrow AF = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\end{array}\]

Similarly, using the triangle QCG, we get \[CH = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\].

The diagonal AC is the sum of the lengths AF, CH, and the diameters of the three circles.

Therefore, we get

\[ \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right) + 2r + 2\left( {2r} \right) + 2r + r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\]

Simplifying the expression, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right) + 2r + 4r + 2r + r\left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right)\\ \Rightarrow AC = \sqrt 2 r - r + 2r + 4r + 2r + \sqrt 2 r - r\end{array}\]

Adding and subtracting the like terms, we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow AC = 2\sqrt 2 r + 6r\\ \Rightarrow AC = r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\end{array}\]

Now, we can observe that triangle ABC is a right angled triangle because the interior angles of a square are right angles.

Let the sides AB, BC, CD, and AD of the square be of length \[x\].

Thus, using the Pythagoras’s theorem in triangle ABC, we get

\[A{C^2} = A{B^2} + B{C^2}\]

Substituting \[AB = BC = x\] and \[AC = r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\] in the equation, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {\left( {r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)} \right)^2} = {x^2} + {x^2}\]

Simplifying the expression, we get

\[ \Rightarrow {r^2}{\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)^2} = 2{x^2}\]

Taking the square root of both sides, we get

\[ \Rightarrow r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right) = \sqrt 2 x\]

Dividing both sides of the equation by \[x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)\], we get

\[\begin{array}{l} \Rightarrow \dfrac{{r\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}}{{x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}} = \dfrac{{\sqrt 2 x}}{{x\left( {2\sqrt 2 + 6} \right)}}\\ \Rightarrow \dfrac{r}{x} = \dfrac{{\sqrt 2 }}{{2\sqrt 2 + 6}}\end{array}\]

We get the ratio of the radius of the smaller circles and the side of the square as \[\dfrac{{\sqrt 2 }}{{2\sqrt 2 + 6}}\].

Note: We used the Pythagoras’s theorem in the solution. The Pythagoras’s theorem states that the square of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is equal to the sum of squares of the other two sides, that is \[{\rm{Hypotenus}}{{\rm{e}}^2} = {\rm{Bas}}{{\rm{e}}^2} + {\rm{Perpendicula}}{{\rm{r}}^2}\]. The hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is its longest side. Pythagora's theorem can be used only in right angled triangles. For other types of triangles, we use Heron’s formula.

Recently Updated Pages

Master Class 11 Computer Science: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Master Class 11 Business Studies: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Master Class 11 Economics: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Master Class 11 English: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Master Class 11 Maths: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Master Class 11 Biology: Engaging Questions & Answers for Success

Trending doubts

One Metric ton is equal to kg A 10000 B 1000 C 100 class 11 physics CBSE

There are 720 permutations of the digits 1 2 3 4 5 class 11 maths CBSE

Discuss the various forms of bacteria class 11 biology CBSE

Draw a diagram of a plant cell and label at least eight class 11 biology CBSE

State the laws of reflection of light

Explain zero factorial class 11 maths CBSE